VPNs

Table of Contents

Trust is a critical component to a thriving digital ecosystems. We trust banks to keep financial information secure; we trust search engines to get us the information we want and map apps to show us the most efficient route. Ironically, virtual private networks, or VPNs, are often a tool for users who lack trust in the practices of other online entities. However, providers of commercial VPN services must still foster trust that they adequately obscure their users’ digital footprints and safeguard their data. CDT is working with VPN providers to create more transparency around their data practices, while empowering consumers to ask important questions before choosing a service.

Introduction

Resources:

- Techsplanations: Part 5, Virtual Private Networks

- Questions for VPN Services

- Unedited Answers: Signals of Trustworthy VPNs

Trust is a critical component to a thriving digital ecosystems. We trust banks to keep financial information secure; we trust search engines to get us the information we want and map apps to show us the most efficient route. Ironically, virtual private networks, or VPNs, are often a tool for users who lack trust in the practices of other online entities. However, providers of commercial VPN services must still foster trust that they adequately obscure their users’ digital footprints and safeguard their data. For many reasons, this has proven challenging for VPNs.

CDT Techsplanations: VPNs allow individuals to disguise and protect their internet traffic. If you would like to know more about how VPNs work, please see our primer on these increasingly prominent privacy-enhancing tools.

A quick search for “VPN” on an app store quickly reveals how opaque and confusing it can be to sort through the number and variety of different VPNs. Many promise additional security and privacy, but as the U.S. Federal Trade Commission has warned, promises alone do not necessarily make a VPN trustworthy. So what does?

CDT convened a discussion at RightsCon in Toronto this spring where IVPN, Mullvad, TunnelBear, and VyprVPN agreed that their industry faces a trust deficit. Coming out of this face-to-face meeting, we have worked with these companies along with ExpressVPN to develop a list of questions that signal basic commitments VPNs can make to signal their trustworthiness and positive reputation.

We have encouraged VPN providers to make their answers, and other resources, easily available on their websites under the heading of “Signals of Trustworthy VPNs” to facilitate easier comparison. The answers from these VPN providers are available here.

The eight questions we’ve put forward focus on (1) corporate accountability, (2) data “logging” practices, and (3) demonstrating good security practices. We hope to add additional VPNs’ answers over time.

The goal of these questions is to improve transparency among VPN services and to help resources like That One Privacy Site and privacytools.io better provide comparisons between different services. We believe VPN providers should be able to easily answer these questions and should do so in an upfront and public fashion. Unfortunately, answering these questions still puts an onus on users to figure out what’s going on, but any VPN that does not put this information front and center is problematic.

Quick Takeaways

Below are the quick takeaways from this work. For more detailed information on each area, proceed to that section in the Table of Contents.

Corporate Accountability

Question 1: What is the public facing and full legal name of the VPN service and any parent or holding companies?

Question 2: Does the company, or other companies involved in the operation or ownership of the service, have any ownership in VPN review websites? Question 3: What is the service’s business model (i.e., how does the VPN make money)?

- Who’s running the show? For commercial privacy and security tools, reputation must matter. A number of VPNs have expressed public support for privacy and digital expression online, and That One Privacy Site even looks to whether a VPN gives back to privacy causes. More important, however, is whether you can put a face behind the company and their expertise. As companies like Facebook, Verizon, and even PornHub operate VPNs, it is important to know not just the individuals in charge of running and securing the VPN but who ultimately owns the company.

- What’s the business model? It’s a cliche now to say if you’re not paying for the product, you are the product. This is especially true with VPNs. Beware of using a free commercial VPN. Operating VPN servers and having the necessary technical and security expertise to run a VPN is not cheap. A VPN should be upfront about how it makes money and any incentives that aren’t aligned with user’s privacy and security interests.

Data “Logging” Practices

Question 4: Does the service store any data or metadata generated during a VPN session (from connection to disconnection) after the session is terminated?

Question 5: Does your company store (or share with others) any user browsing and/or network activity data, including DNS lookups and records of domain names and websites visited?

Question 6: Do you have a clear process for responding to legitimate requests for data from law enforcement and courts?

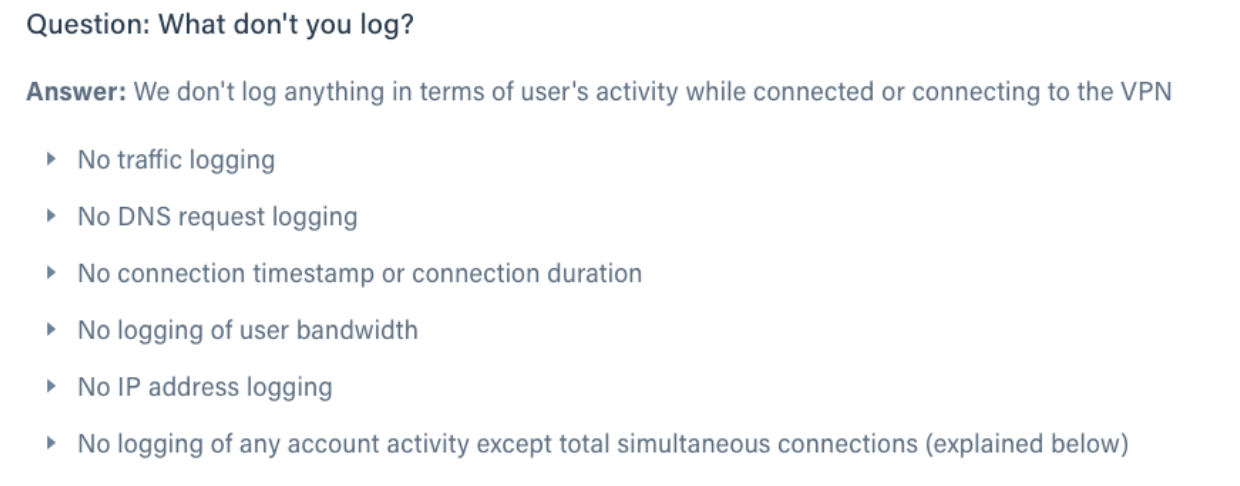

- What’s the VPN say about “logging” practices? Logging practices are akin to the third rail of VPN politics, and the logging practices of different VPNs are confusing. VPNs often trip over themselves to make broad “no logging” claims that have turned out to be inaccurate time and time again. Logs can generally be divided into connection and activity logs, but there is no standard definition of what constitutes a log. What is relevant is what information can be tied back to a user. This can include:

- Traffic activity (like downloads)

- DNS requests (details of what websites are being visited)

- Connection timestamps (reveal when a user was online)

- Bandwidth logging (reveal how much data was used, which can be used to guess what devices were being used or even what movie was being watched)

- IP addresses

- Logging this information can be useful for troubleshooting purposes, but any information that can be kept after a VPN session ends is a privacy risk. A responsible VPN is very up front about what it means by logging and what data it retains over time, even if it is aggregated or anonymous. This should be at the top of any privacy policy or terms of service. It should be separately disclosed and easily discoverable via the VPN’s website or app.

- What about law enforcement and government surveillance? Many people use VPNs to avoid the watchful eyes of government intelligence agencies, and countries like China and Russia have passed laws to restrict and ban VPNs. VPNs can be a useful tool in places where dissidents are prosecuted, but this has created a situation where VPNs often find themselves in tension with law enforcement and government surveillance generally. As a result, many resources highlight the legal jurisdiction the VPN falls under, especially noting whether servers are located in “5-9-14 Eyes Jurisdictions,” which are countries that share digital intelligence. But no one should expect a VPN to provide a perfect defense against nation-state level surveillance. Again, a VPN cannot guarantee anonymity. However, a VPN’s physical location and the national law it operates under can afford users different privacy protections and does dictate how a VPN might respond to a government request for data. CDT recommends that VPNs, at minimum, provide transparency reports about how often they receive court orders and other government requests and have a clear process in place for responding to any requests for data.

Demonstrating Good Security

Question 7: What do you do to protect against unauthorized access to customer data flows over the VPN?

Question 8: What other controls does the service use to protect user data?

- How does the VPN think about security? An individual cannot assess the actual security practices of a VPN. This is especially problematic since it is often a primary marketing point for the company. However several practices are particularly important:

- Auditing: There has been much talk of the need for independent security audits among VPNs, but audits are neither cheap nor easy to do. Many VPNs either want assessments done on the cheap or the results are so problematic that nothing is ever revealed publicly. When CDT first began speaking with VPNs, only TunnelBear had undergone security audits where its auditor, Cure53, also released information about the problems it uncovered. Subsequently, we also saw Mullvad undergo an audit with Cure53 in addition to VyprVPN undergoing a logging audit by Leviathan Security Group.

- “Bug Bounty” and Vulnerability Handling Programs: A “bug bounty” program encourages security researchers and other technical experts to identify and report vulnerabilities they might uncover when using a VPN service. But a bug bounty program is only one part of a larger vulnerability handling program, which includes a point of contact, follow-up, an establishing a software development lifecycle that ensures flaws are addressed. Bug bounties are no replacement for ongoing penetration testing of the VPN.

- Encryption Protocols: VPNs use a dizzying array of cryptography to protect traffic, and not all the choices providers make with respect to encryption are the same. While average users will not be able to evaluate information about cryptographic mechanisms, they should be disclosed so that security experts and technical users can assess what practical level of protection a service provides. For example, some VPNs use lower security (L2TP-PSK) encryption protocols that may share an encryption key for man or all users, reducing the practical security offered by the service.

- Software Updating and “Patching”: VPN services address what mechanisms are in place to attempt to quickly fix flaws in either VPN software maintained by the provider or other support tools.

- Server Control and Physical Security: Physical security and control over servers can also be an issue. Knowing who is operating and securing the servers being used by a VPN is useful information. VPNs should also provide some detail into how they physically protect their infrastructure and train employees.

More can be done. As we and others have noted, security and privacy audits are badly needed in this industry, but truly independent assessments require significant resources. Specific technical features and security choices were outside of the scope of these questions, but CDT would encourage all VPN providers to declare baseline privacy and security features and processes, provide more insight into their corporate structure and business practices, and then invite third parties to verify these practices.

What follows builds on the set of questions the group agreed to answer and offers CDT’s perspective on the issues raised by each question.

Corporate Accountability & Business Model

Fly-by-night operations and the ease with which a VPN service can be set up as a scam have contributed to a lack of trust in the VPN ecosystem. MotherBoard has investigated how phony VPN services have seized on the public’s privacy concerns; RestorePrivacy has a growing “warning list” of VPNs.

Another issue is to be aware of is are “white label” VPN services. For example, when Verizon recently announced it would be launching its own paid VPN service, the underlying technology is operated by McAfee. Similarly, adult website Pornhub recently announced that it would offer a VPN service, VPNhub, that appears to be a product of StackPath. White label VPNs are not necessarily a bad thing, but they further muddy an ecosystem where reputation is both important and difficult to track.

One concrete way a VPN provider can build trust is to be public-facing about its operations and ownership. When reviewing VPN services, Wirecutter went so far as to acknowledge that it would “rather give up other positives—like faster speeds or extra convenience features—if it meant knowing who led or owned the company providing our connections.” A number of the questions trustworthy VPNs should be able to answer attempt to address this by asking VPN providers to answer the following:

Question 1: What is the public facing and full legal name of the VPN service and any parent or holding companies?

Question 2: Does the company, or other companies involved in the operation or ownership of the service, have any ownership in VPN review websites?

This information can help establish the legal credibility of a service and its connection to other platforms, services, or security companies. CDT recommends that VPN providers also display information about the company’s leadership team, which can help users know more about the reputations of who they are trusting with their online activities:

Ex.: Mullvad provides details of its owners and employees.

Unclear ownership presents recurring issues for VPNs. For example, before it was removed from the Apple App Store, Onavo came under tremendous criticism for being a VPN application that was actually owned by Facebook — and used for business intelligence.

To that end, VPN providers should also provide any information as to whether the company, or other companies or individuals involved, have ownership and economic states in other companies. This should include clear disclosures of any separate produce lines, brand names, and any other economic interests among corporate leadership.

Unfortunately, VPN review websites themselves have proven especially susceptible to abuse. CDT recommends that VPNs disclose whether or not they operates other VPN services or have stakes in VPN or other technology review websites.

Legal jurisdiction of VPN providers have become another important issue in light of Edward Snowden’s revelations of global mass surveillance. While users frequently wish to avoid VPN providers based in what are known as the “5-9-14 Eyes Jurisdictions,” we should be clear: no one should expect a VPN service alone to provide a perfect defense against nation-state level surveillance. Jurisdiction information is still useful, as the Electronic Frontier Foundation points out, because the VPN provider’s place of incorporation and the national law it operates under may afford users different protections such as general privacy laws, data retention requirements, and security obligations. It also dictates how providers may respond to legal requests for data.

Ex.: VyprVPN clearly explains its place of incorporation.

CDT recommends that any VPN provider should be able to disclose their place of legal incorporation and the laws they operate under. VPN providers should also provide a physical mailing address and other direct contact information for users.

Ex.: TunnelBear provides an address for its place of operation.

Question 3: What is the service’s business model (i.e., how does the VPN make money)?

Another key concern with any VPN is how they make money. While VPNs are commonly considered a privacy-protecting tool by users, it is important to recognize that the company that runs a VPN service is in a position of being able to see a user’s internet activities and network traffic. VPN providers can easily monetize this information, which has led to the proliferation of free VPN services.

An interesting, arguably notorious example of this is Hola, which is a “free VPN” where users access the VPN in exchange for providing network bandwidth. (The VPN also discloses in its privacy policy that it collects information about any website accessed on the service, which is why logging practices are so important to pay attention to.) These sorts of business models often stand in sharp contrast to VPN marketing materials which position them as privacy- and security-enhancing products.

CDT believes that individuals should be given detailed information about a VPN provider’s business model, specifically whether subscriptions are the sole source of a service’s revenue. To confirm these statements, VPN providers should undergo regular independent audits of their finances and provide public summaries that detail general revenues and costs of providing the service.

Logging and Data Collection and Retention Practices

If individuals are concerned internet service providers (ISPs) might monetize their data, that same concern exists with VPNs. VPN providers essentially stand in place of an ISP and, as a result, are in a position to see user’s internet activities and network traffic. VPNs often address these concerns by making broad “no logging” claims. Logging practices have become especially contentious and confusing as a result.

VPN logs can be divided generally into connection and activity logs. Activity (or usage) logs include online activities including not only web browsing history (what you looked at and clicked on, when, and for how long) but also other network traffic information including voice, video, or P2P sharing. Connection logs can include a variety of technical information, including the time a connection is established, timestamps generally, amount of data transferred during a session, and IP addresses. Activity logs can be especially sensitive, and many providers claim to log either a minimal amount of data or no data with respect to the connection logs. But here’s the problem: there’s often not a standard definition of what constitutes a log. If a VPN logs enough metadata and connection information, they can still know (and a reveal) a lot of information about your online activities.

The other issue is not just whether this information can conceivably be collected but whether it is kept. Logs themselves can serve legitimately useful operational or troubleshooting purposes. However, any information that is retained after the end of a VPN session can represent a privacy risk to users depending upon their threat model. VPN providers should be able to answer the following:

Question 4: Does the service store any data or metadata generated during a VPN session (from connection to disconnection) after the session is terminated?

Question 5: Does your company store (or share with others) any user browsing and/or network activity data, including DNS lookups and records of domain names and websites visited?

Transparency is no panacea, but a VPN provider should be upfront and clear about their logging practices. Specifically, CDT believes:

- VPN providers should clearly disclose exactly what they mean by “logging.” This includes both connection and activity logging practices, as well as whether the VPN provider aggregates this information. Far too often, VPN providers provide bolded “no logging” claims with caveats detailed in terms of service or “privacy policies”. Individuals must be able to easily understand the logging policy for both connection and activity logs in order to evaluate a VPN service. If that is difficult or confusing, the VPN provider should de better.

Ex.: IVPN’s privacy policy dedicates a section to explaining what the VPN means by “logless.” - VPN providers should be clear whether their service stores any data or associated metadata from a VPN session after the session is terminated, and what this data entails.

- VPN providers should disclose their approximate retention periods for any log data. Mature organizations have formal internal processes that detail when a company disposes of different data types. VPN providers can put in place procedures for automatically deleting any retained information after an appropriate period of time, and this period of time should be publicly disclosed. If a VPN is keeping data for any period of time, it should disclose this and justify the length of time.

A VPN’s privacy practices can also be distinguished from logging and retention policies. This includes policy-level questions about how data can be accessed, used, or shared both internally and with outside third parties.

Distinct from security issues and related to logging and retention policies, VPN privacy practices also warrant scrutiny. This includes how data can be accessed, used, or shared with third parties. VPN providers should have an answer to the following question:

Question 6: Do you have a clear process for responding to legitimate requests for data from law enforcement and courts?

A responsible VPN provider will answer “yes” to this question, but these procedures should be made available publicly, such as through a transparency report. Some VPNs have also put in place creative warrant canaries that attempt to signal if a search and seizure has occurred.

CDT also recommends that VPN providers:

- Have a clear process in place for responding to legitimate requests from law enforcement and courts.

- Disclose information about ownership, control, and physical location of a VPN providers’ DNS servers. Specifically, VPN providers should also explain what measures they have in place to protect data in the event of third parties gaining physical access to equipment or servers.

- Provide privacy policy disclosures that provide disclosures meeting the threshold required by the EU General Data Protection Regulation. While transparency alone is not ideal to improve privacy awareness, privacy policies that echo GDPR requirements and established practices should provide further disclosures than current practice.

Data Security Protections

Assessing the security of VPN services has proven challenging. As ArsTechnica explained two years ago, it felt unable to recommend VPNs that could guarantee the security of users. Researchers and academic studies have repeatedly highlighted security lapses in VPN services, from data leakage to unencrypted traffic. VPN providers should provide information about their data security practices, including what encryption and authentication protocols they use and whether they deploy software/hardware hardening.

Data security is an evolving target, but VPN users are frequently interested in incredibly strong security. The final two questions offer an opportunity for VPN providers to explain their security practices:

Question 7: What do you do to protect against unauthorized access to customer data flows over the VPN?

Question 8: What other controls does the service use to protect user data?

As the questionnaire answers revealed, VPN providers go about answered this questions in very different ways. CDT recommends the following:

- VPN providers should implement “bug bounty” programs to encourage third parties to identify and report vulnerabilities they might uncover when using a VPN service.

Ex.: ExpressVPN clearly discloses its process for taking receiving bugs.While CDT supports bug bounty programs, vulnerabilities can still get through. VPN providers should have clear processes for the circumstances in which in VPN provider discloses to users a vulnerability or security issue.

- VPN providers should undertake independent security audits to identify technical vulnerabilities. Third-party auditing of VPN claims is not a new idea, and some VPNs have engaged in security audits. Independent audits are time-consuming and costly and one recurring issue is whether and how results can be made available to the public. Basic elements of a security audit should include information about the audit, including the name of the auditor and its personnel, its expertise, and the scope of the audit and/or any limitations placed on auditors. We would recommend that even if audits are directed or limited in scope, they should entail at minimum complete access to the VPN provider’s systems and code.

Ex.: Cure53 provided a summary report of its audit into TunnelBear. - Incorporation of open source code into a VPN product may ensure that security experts can quick improve and patch vulnerabilities. A system for ongoing monitoring of systems is important. Some vulnerabilities may not be easily patched, which is vulnerability disclosure processes are so important.