NLRB Memo Takes Aim at Intrusive Workplace Surveillance & Algorithmic Management Systems

Recently, Jennifer Abruzzo, the General Counsel for the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), released a memorandum representing the first significant federal regulatory guidance confronting the harms that intrusive electronic surveillance and management systems inflict on workers. Workers’ rights advocates have expressed increasing concern about these systems in recent years as companies deploy them to surveil and manage workers. Last year, CDT wrote a report on the impact of intrusive “bossware” systems on workers’ health and safety and called for regulatory action to help protect workers from the harmful effects of intrusive and nearly continuous worker surveillance systems.

Abruzzo’s memorandum focuses on companies’ use of surveillance technology to disrupt union organizing efforts, an issue that many labor and worker advocacy organizations have highlighted. Specifically, the memorandum addresses how intrusive and sophisticated electronic surveillance and management systems could interfere with employees’ rights under Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), which protects employees’ right to cooperate and band together to improve working conditions or unionize. In the memorandum, Abruzzo said that she would urge the NLRB “to apply the Act to protect employees, to the greatest extent possible, from intrusive or abusive electronic monitoring and automated management practices that would have a tendency to interfere with Section 7 rights.” The memorandum represents the most significant step by federal regulators to date toward reining in the widespread, harmful use of surveillance systems.

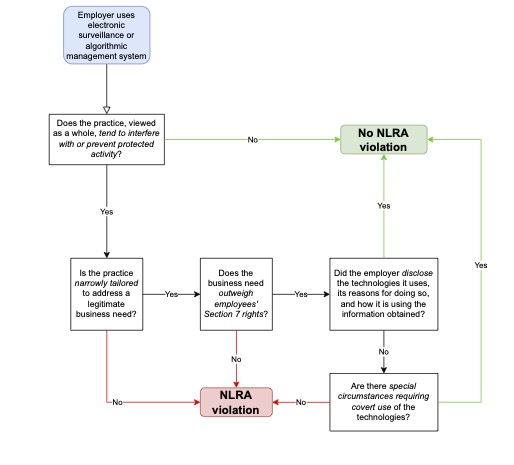

The memorandum lays out a multi-pronged test for determining whether an employer’s surveillance and management practices violate the NLRA:

- Determine whether the practices, “viewed as a whole, would tend to interfere with or prevent a reasonable employee from engaging in activity protected by” the NLRA. If not, then, the memo implies, the practices would not violate the NLRA.

- If the practices would tend to interfere with Section 7 rights, then the employer must establish several things before the use of the technology is permissible:

- “[T]hat the practices at issue are narrowly tailored to address a legitimate business need—i.e., that its need cannot be met through means less damaging to employee rights.”

- That the business need “outweighs employees’ Section 7 rights”

- That the employer discloses to employees “the technologies it uses to monitor and manage them, its reasons for doing so, and how it is using the information it obtains.”

- An employer can only withhold such notice if it “demonstrates that special circumstances require covert use of the technologies.”

Abruzzo’s memorandum also lays out a number of specific categories of practices that she said could interfere with workers’ right to organize; we have added (in italics) hypothetical examples of existing workplace surveillance and management technologies that would fall under each category:

- Using surveillance specifically to monitor protected activities

- Example: An employer installs software that monitors workers’ emails and chats, and alerts managers if a worker’s messages include words like “union” or “protest.”

- Introducing new monitoring technologies in response to protected activities

- Example: After a group of workers jointly write managers to protest overtime policies, the employer installs cameras in break rooms and new monitoring software on their computers.

- Disciplining workers “who concertedly protest workplace surveillance or the pace of work set by algorithmic management.”

- Example: A company terminates several employees who protest the employer’s introduction of a new system that takes screenshots of workers’ laptop screens throughout the workday.

- Using a hiring or management algorithm that discriminates against workers that engage in protected activity (or based on a prediction that they might do so)

- Example: A company’s HR department adopts a new resume scanning program that penalizes workers whose resumes indicate prior union membership or interest in workers’ rights.

- If workers are unionized, failing to provide information about tracking technologies or failing to bargain over them

- Example: The employer in a unionized workplace installs new location monitoring software on employees’ phones without informing the union, thus depriving the union of the opportunity to negotiate regarding the use of location monitoring during collective bargaining.

- Using electronic surveillance and a “breakneck pace of work” that “severely limit[s] or completely prevent[s] employees from engaging in protected conversations about unionization or terms and conditions of employment.”

- Example: A logistics company uses algorithmic management systems that monitor and penalize employee downtime, including time spent in break rooms or communicating with other workers.

The memorandum is a significant milestone in the fight against the harmful effects of intrusive electronic surveillance and management systems. But the key advance will be if the Board adopts Abruzzo’s analysis and uses its authority to crack down on the uses of bossware and other intrusive surveillance and management practices that interfere with workers’ Section 7 rights.

Notably, Abruzzo closed the memorandum by emphasizing her commitment to “an interagency approach on these issues, as numerous agencies across the federal government” are examining the lawfulness of these workplace technologies. Such a multi-agency response will be essential because no single agency has the breadth of authority necessary to regulate the full array of harms that bossware and related technologies can cause workers.

CDT will continue to support such efforts, as it did last week when we submitted extensive comments–including comments on bossware and other workplace surveillance–in response to the Federal Trade Commission’s Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on commercial surveillance practices. If the FTC and other agencies follow Abruzzo’s lead, the NLRB memorandum could–and hopefully will–be merely the first salvo in a federal response to employers’ increasing use of these exploitative technologies.

###