European Policy, Free Expression, Government Surveillance, Privacy & Data

How can we apply human rights due diligence to content moderation? Focus on the EU Digital Services Act – Event Summary

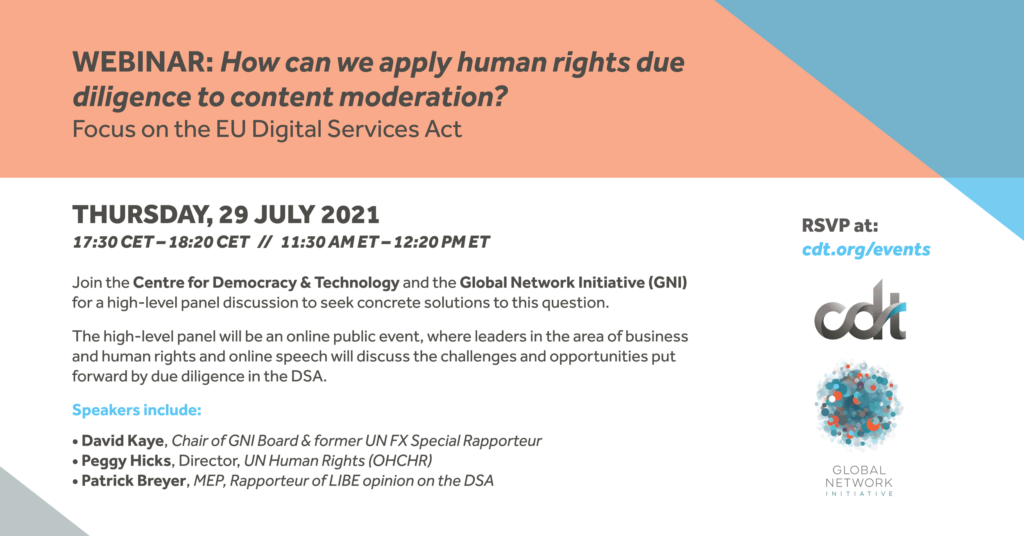

On 29 July 2021, the CDT and the Global Network Initiative (GNI) organised a high-level panel discussion to seek concrete solutions to the below questions.

- What are the potential opportunities and challenges with the current proposed due diligence regime in the DSA?

- What similarities and differences are there in business and human rights due diligence for supply chains vs. due diligence for online speech ?

- What lessons can be learned about how best to verify and share lessons from human rights due diligence?

- What would be the best human rights due diligence model for the DSA?

Moderator:

- Iverna McGowan, Director of the Europe Office, Centre for Democracy & Technology (CDT)

Speakers:

- David Kaye, Chair of the Global Network Initiative Board and former UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression

- Peggy Hicks, Director, UN Human Rights (OHCHR)

- Patrick Breyer, MEP, Rapporteur of the LIBE opinion on the DSA

Key Messages:

- The DSA offers an opportunity to focus on due process, transparency, and public access to information.

- It will be essential to get the balance between the role of companies and governments right. Both need checks on their power.

- The full spectrum of human rights needs to be respected, including the right to non-discrimination, which is frequently infringed by automated content moderation systems.

- Digital examination, not exceptionalism. We must apply existing human rights norms to our online world.

- Article 26 on due diligence must include a clearer obligation for companies to adopt a human rights lens to the impact of their products and services. This should include scrutinising government-ordered take-down requests and resisting those that are not compatible with human rights.

- The DSA itself should be subject to a human rights impact assessment so that its impact can be identified, monitored, and corrected if necessary.

- We should use the DSA to rethink how judicial oversight can be effectively built into online content moderation.

- Having law enforcement authorities designated as trusted flaggers raises serious human rights concerns.

- We need to avoid a situation where the DSA creates a shadow set of norms that are privately determined according to private interests, and instead focus on how to ensure that the public interest prevails throughout.

Importance of human rights to content moderation

David Kaye opened the discussion with an appeal to lawmakers to use the EU Digital Services Act as an opportunity to go beyond normative questions relating to individual pieces of content and to focus more attention on the broader issues of due process rights, transparency, and the public’s access to information. EU lawmakers should also interrogate to what extent it is appropriate for them alone to make decisions on content.

Peggy Hicks recalled how useful the human rights framework can be, but stressed that we need to invest the time to think through how the norms apply in practice. She called for digital examination, not digital exceptionalism – human rights norms should not be altered to fit the digital space, we must work through how to apply those norms in the digital space. She stressed the need to get the balance between the roles of government and companies right. Hicks cited the example of the recent controversy regarding racism in sport and voiced concern that by exclusively placing the blame on companies, we miss the opportunity to interrogate the root-causes of racism in society and to hold the government to account on their efforts to combat it. She also appealed to EU lawmakers to pay special attention to the global impact that EU legislation could have, and gave the example of how the German NetzDG law has been replicated in other countries, including in settings where it has had an adverse human rights impact.

Patrick Breyer recalled how valuable input from human rights experts is to the LIBE Committee. He stressed the importance of the right to freedom of expression to protect against government removal orders. He cited the example of a case where the French law enforcement authorities ordered the removal of thousands of pages from the Internet Archive, and due to the overly broad and unclear definitions of ‘terrorism’ upon which the requests were made, ultimately this led to the removal of many pages of legal content. He stressed the crucial role that courts need to play. In France, the Avia law was struck down by a court for non-compliance with fundamental rights. The European Court of Justice helps to harmonise the EU regional response to content questions. Human rights are indeed also about procedural rights. On the day of the event, a top German civil court ruled against Facebook for its failure to give a hearing to a publisher in advance of removing their content. Clearly procedural rights need to be a starting point.

What should due diligence look like in relation to content moderation?

Peggy Hicks outlined how the fragmentation in approach can pose challenges, with approaches differing State by State and company by company. Technology companies already have a responsibility to respect international human rights law in the way they do their business and must apply due diligence. This due diligence should include examining how their platform might perpetuate harmful behaviour or enable incitement to violence through amplification or targeting. Mitigation measures should be proportionate to the identified risk. The challenge is that the due diligence provisions in the DSA are overly focused on how companies comply with take-down requests, not on respecting human rights. In fact, a key element of a company’s due diligence should actually be resisting such requests, including government orders when they do not comply with human rights. In this context, it is important to note that there are a variety of ways that companies can engage that do not include removal, including labelling, reducing amplification, etc. We need to continually assess the adverse human rights impact of content moderation systems and their application. To achieve accountability we need transparency, communication, tracking, and independent auditing.

David Kaye drew attention to Article 26 of the DSA, which frames the ‘risk-assessment’ obligation. An important fix to this provision would be the framing of the obligation to use the human rights lens to reflect on the impact of companies’ products and services on human rights. The current language in Article 26 on ‘illegal content’ is potentially problematic. There is a lot of ambiguity between what is actually illegal and what content must be removed under the voluntary codes proposed in the DSA. The idea of human rights impact assessments for companies could help. These assessments should be made public and open to scrutiny, which will help improve the understanding of the impacts of content moderation.

Patrick Breyer expressed concern that these provisions on due diligence in the DSA aim at increasing the pressure on intermediaries to self-police their content, or self-judge the legality of it. The DSA should aim at curtailing the power of these platforms, but the draft conversely gives them more power through the responsibilities and obligations placed upon them. Although the safe harbour provision does remain intact, under Art. 14, once an intermediary receives a well substantiated notification, that would amount to ‘actual knowledge’ sufficient to defeat the safe harbor. The LIBE Committee proposes to delete this dangerous provision. He also expressed concern at cross-border removal orders, which could lead to a race to the bottom for speech in Europe and possibly beyond. This is why we must limit the territorial effect of removal orders.

Online Civic Space and Government Accountability

Peggy Hicks highlighted that whilst the DSA is suggesting human rights impact assessments for platforms, it should also include human rights impact assessment for the legislation itself. Meanwhile, the provision on trusted flaggers is a real concern for UN Human Rights. UN Human Rights is part of many trusted flagger networks and believes it is a model that can work well when independent organisations are involved. It is very concerning, however, that law enforcement authorities would have that authority. There are especially serious implications for human rights if this model is replicated abroad.

David Kaye examined the role of the proposed digital services coordinators. He expressed concern at the lack of specified legal process and in particular that such a system could mean that independent judicial oversight would no longer be the norm. This would represent a missed opportunity to rethink how judicial oversight can be effectively built into online content moderation. There are not enough constraints on the digital services coordinators’ powers, nor enough thought about how courts can play a more active role. Given how central content moderation is to a host of human rights, government agencies engaging in these processes should also be subject to auditing, public hearings, and legislative oversight.

Patrick Breyer said that the LIBE Committee is proposing that removal orders be reserved for courts. Law enforcement is not appropriate to carry out the necessary balancing of interests. He expressed concern about the codes of conduct (“soft law”) through which companies voluntarily agree on certain rules, since these arrangements are not directly bound by fundamental rights. The process on such codes should be much more transparent and inclusive. Civil society should be at the table and the European Parliament and Council should also have a role. There should be no obligation to remove content even if flagged by a trusted flagger, though the overly broad intermediary liability provisions in Art. 14 in the European Commission draft does lead to concerns here.

On managing judicial review at scale, Peggy Hicks pointed out that the problem exists regardless of whether it’s addressed through dispute resolution bodies, administrative bodies, or judicial review. There are ways to bring in judicial review in a more adequate way. Under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, it is clear that there is a responsibility for companies to have grievance mechanisms. Rights-holders need to be involved in the design and oversight of such mechanisms. It’s not just privacy or freedom of expression that are affected, but a broader set of rights. For example, we know that automated content moderation disproportionately impacts minority groups. We must keep the right to non-discrimination central to our thinking.

Peggy Hicks again stressed the importance and value of using a human rights lens. Let’s look at the right to non-discrimination. Content from marginalised groups will be disproportionately taken down, especially when automated tools are used. Liability of companies’ legal representatives as part of due diligence would set a dangerous precedent, is unnecessary, and again is likely to be copied globally. It is also important to think about legal content. What is required with respect to trusted flaggers? Will incentives for platforms to act against legal speech be created? The human rights lens needs to be applied and used for assessment along the way. The draft DSA does bring in really positive elements, yet issues remain, including around definitions and risks of repressing the vital and legitimate speech of human rights defenders and journalists, which is why it’s so important to get the framework right.