ECPA Reform: Our Private Communications Deserve the Gold Standard

Yesterday, the Senate Judiciary Committee conducted a hearing to discuss amending the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) – an Act in desperate need of reform in light of the many technological innovations and developments that have proliferated since 1986, the year it was passed. The ECPA reform process was meant to bring the statute up to par with what the vast majority of Americans expect and are entitled to: the same protections for their personal emails, text messages, and other private Internet communications as those afforded to their private letters locked away in a desk.

Unfortunately, administrative officials used this opportunity to ask for less protection, so that civil law enforcement officials can obtain private Internet communications at a lower standard, and in many more circumstances. Especially on days like today, which happens to be our national Constitution Day, it is critical to recognize the fundamental differences between warrants and subpoenas, and reject any notion that our most personal, private, and intimate conversations deserve less privacy simply because they are now in digital form.

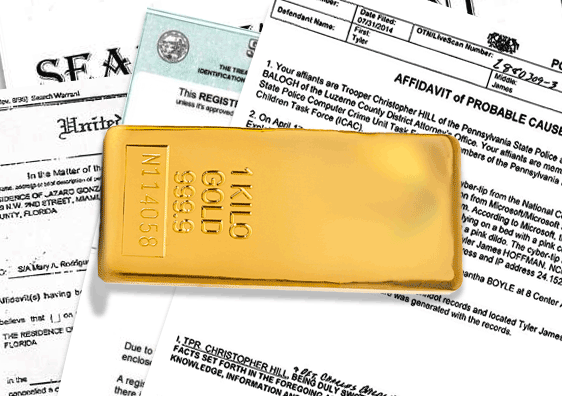

ECPA reformers want email held by your ISP to be protected by a warrant requirement. The warrant is considered the “gold standard” for privacy protection in the U.S., which is why it is embedded in the Fourth Amendment of our Constitution (which prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures). Searches that are the most invasive in kind, such as a search of your home or your personal belongings (including your letters), must generally be conducted with a warrant rather than an instrument that requires a lower standard of review. When a warrant is required, the government must approach a judge or magistrate and demonstrate probable cause to believe that specific evidence related to a crime is currently in the specific place to be searched. The warrant itself is very narrow in scope – it must specify the place to be searched and the things to be sought. All other places and items, unless in plain view during the search, cannot be touched.

Administrative agencies don’t want the gold standard to protect your email, they want a much lower bar: a court order issued on a lower (but unspecified) standard to conduct much broader investigations. Right now, those agencies issue subpoenas, so it is a fair bet that the standard they seek will be as close as they can make it to the subpoena standard. When obtaining information with a subpoena, the government need only believe that the customer records sought are relevant to an investigation. As a result, the subpoena is by far the easiest instrument for the government to use. It is also the broadest in scope, because many, many things can be arguably “relevant” to an investigation.

To make matters worse, the court orders they are seeking could be used to obtain email content relevant to any civil infraction, not just the limited circumstances involved in a criminal context. The government could obtain information relevant to misfiling your tax returns or violating the health code, for example. In addition, subpoenas can be directed not only at people subject to the investigation, but also to any witnesses with relevant information. Worst of all – this authority is both unnecessary and likely unconstitutional. A 2010 appeals court decision, US v. Warshak, made clear that email content enjoys a reasonable expectation of privacy under the Constitution and the proper authority for accessing email content is a warrant. Both the SEC and the FTC have admitted that since Warshak, neither has tried to use subpoenas to access email content. Yet, they continue to conduct robust investigations.

In short, this amounts to an unconstitutional solution to a nonexistent problem – one aimed at getting an unprecedented level of access to many Americans’ email inboxes. Surely our private communications deserve better. On Constitution Day, let’s hope that lawmakers recognize the “right of the people” to be secure in their “papers and effects,” even if those papers and effects are now online.