Government Surveillance, Privacy & Data, Reproductive Rights

Cracking Down on Federal Aid for Reproductive Health Surveillance: Fusion Centers

This is the third in a series of blog posts examining how the federal government and the White House — which has pledged to fight the criminalization of abortion — can prevent federal surveillance assistance to state and local law enforcement from being used to investigate and prosecute reproductive health care choices. Our first two posts examined Regional Computer Forensic Laboratories — where federal officials help state and local law enforcement to access and analyze electronic devices — and the National Domestic Computer Assistance Center, a federal entity that helps local law enforcement collect communications content and other records from companies.

Fusion centers are law enforcement hubs that stockpile and share data to aid state and local investigations. At least 80 fusion centers operate across the country, with at least one in each state. They are owned and operated by the states and nearly all staff at facilities are from state and local agencies. However, fusion centers significantly rely on the federal government, which can leverage that reliance to ensure that its assistance is not used to facilitate abortion-related investigations.

What data do fusion centers collect and provide to law enforcement?

Fusion centers simultaneously serve as a means for local law enforcement entities to receive and use information from others, and to share broadly their own data and records with other law enforcement agencies.

Data disseminated and received by fusion centers can include noncontroversial records — such as booking logs — but also huge swaths of information that are invasive or built from unreliable and biased sources. Most notably, data harvested from social media monitoring is stored and shared via fusion centers, a practice that has often seeped into monitoring peaceful protests and other First Amendment-protected activities. For example, fusion centers have been used to catalog and distribute attendance lists for civil rights protests, social media info on Black Lives Matter organizers, and details on events such as a Juneteenth community festival.

Numerous fusion centers store and disseminate location information that is purchased from data brokers. Others catalog data from automated license plate readers and cell phone tracking surveillance powers. A report on the fusion center in Austin, Texas, discusses use of data mining services to stockpile data generated from everyday activities such as the use of utilities, motor vehicles, cell phones, and social media.

Fusion centers also collect and disseminate reports for a Suspicious Activity Reporting Initiative meant to identify potential criminal activity. These reports can be based on police interactions with the public or tips and call-ins to law enforcement. As such, reports can be baseless, or built on discrimination. For example, a 2020 Open The Government report documented numerous cases where reports from a local “If You See Something, Say Something” campaign were “filled out on suspicious males based in part on their ethnic origin” and then disseminated via a fusion center. And in 2020, leaked documents showed that fusion centers distributed far-right conspiracy posts about Black Lives Matter protests, with law enforcement labeling the unfounded claims as “open intelligence” of violent threats.

What areas do fusion centers focus on?

Fusion centers were established in the aftermath of the September 11th attacks in order to facilitate information sharing for counterterrorism purposes. They were supposed to help law enforcement “connect the dots” to uncover terrorists’ plans. However, their role has morphed far beyond that original goal, and fusion centers are now used for a wide range of law enforcement activities. A majority of them include general crime and narcotics as “top areas of focus” according to the most recent National Network of Fusion Centers’ annual report.

This expansion in the types of crimes of interest to participants in fusion centers has, in turn, broadened the information they collect. In fact, according to a Brennan Center report, a majority of the information collected by fusion centers today has no connection to terrorism.

How the federal government supports fusion centers

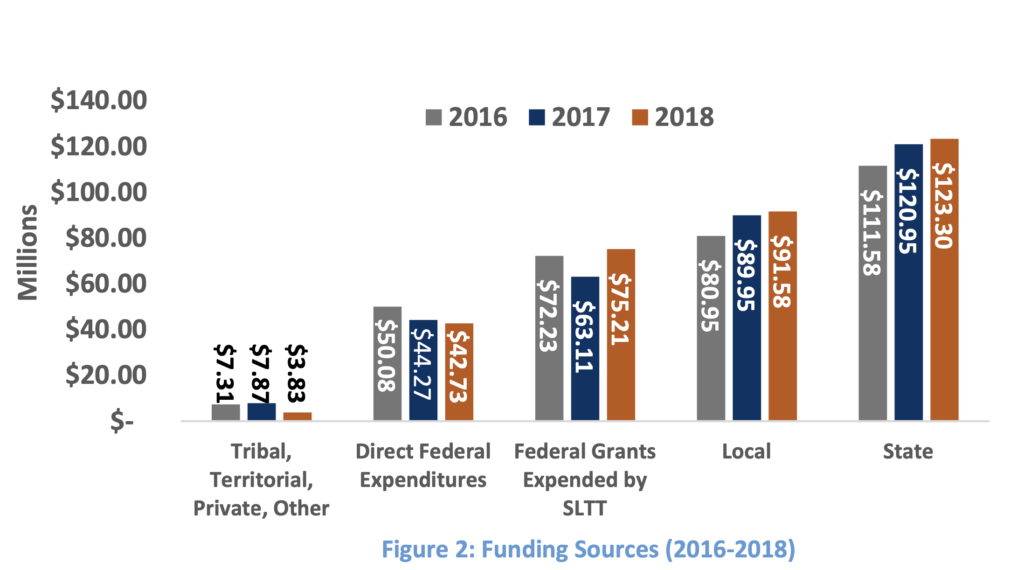

Despite being state-owned and operated, fusion centers are highly dependent on the federal government. Federal funds comprise over one-third of all fusion center funding. Certain centers rely on federal dollars for an even larger portion of their budget: According to Mike Sena, President of the National Fusion Center Association, “some centers are nearly entirely grant funded” by a set of Department of Homeland Security grants.

In addition to funding, the federal government provides fusion centers with valuable data and the means of disseminating and receiving information. Nearly all centers have access to the Homeland Secure Data Network, the Federal Bureau of Investigation Network, or both (these are tools for sharing classified information, such as case files and intelligence reports, from DHS and the FBI, respectively). Fusion centers also access:

- The Homeland Security Information Network (HSIN), which allows personnel at fusion centers “to access homeland security data, send requests securely between agencies, manage operations, coordinate planned event safety and security, respond to incidents, and share the information,” according to Mike Sena;

- The FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS), a self-described “high-tech hub” which manages the FBI’s crime information databases, including the National Crime Information Center, the National Data Exchange, the Law Enforcement Enterprise Portal, Uniform Crime Reports, and Next Generation Identification; and

- The Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), a bureau within the Treasury Department designed to combat money laundering and financial crimes by collecting, analyzing, and disseminating financial and transactions data, such as required reporting by banks on customers’ financial activities.

How fusion centers could be used for abortion surveillance

Given the huge range of data that is funneled into and through fusion centers, there are a host of ways theys could provide data and information to support abortion investigations conducted by state authorities. Cell phone location data as well as logs from automated license plate readers could be used to track visits to clinics. Community surveillance that bounty laws may prompt could result in tips and call-ins to fusion centers about medical practices by doctors, pregnancy status of individuals, and plans to end pregnancies.

Fusion centers’ practice of sharing data across states could prove especially useful to law enforcement if they attempt to enforce their abortion bans across state lines, giving them sources of intelligence outside their own jurisdiction.

Fusion centers’ significant use of social media information could also help states enforce laws against aiding and abetting abortions. Since the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, there have been broad efforts to provide support for individuals seeking reproductive health services such as offering “camping” as a coded term for offering lodging to individuals traveling to receive an abortion, or providing abortion medication via mail. Social media monitoring could catalog these activities and fusion centers could give law enforcement officials in states with abortion bans tremendous reach to find individuals who they might claim have violated aiding and abetting laws.

How the federal government should respond

Federal support for fusion centers is largely based on two grant programs: the State Homeland Security Grant Program and the Urban Area Security Initiative, both of which were established to support counter-terrorism efforts. Fusion centers owned and operated by states that currently ban abortion receive massive support through these grants.

| STATE | FUNDING | STATE | FUNDING |

| Alabama | $4,847,500 | Missouri | $10,147,500 |

| Arkansas | $4,847,500 | Oklahoma | $4,847,500 |

| Arizona | $10,097,500 | South Dakota | $4,847,500 |

| Georgia | $11,988,656 | Tennessee | $4,847,500 |

| Idaho | $4,847,500 | Texas | $63,510,451 |

| Kentucky | $4,847,500 | West Virginia | $4,847,500 |

| Louisiana | $6,347,500 | Wisconsin | $4,847,500 |

| Mississippi | $4,847,500 |

Fiscal Year 2022 Allocations; State list based on New York Times reporting as of October 5, 2022.

The Department of Homeland Security could put added emphasis on ensuring these grant funds are generally focused on counterterrorism rather than an unrestricted set of purposes. This principle could guide how the federal government — which originally established fusion centers only to facilitate investigation of terrorism — conditions its funding. It could make federal funding contingent on commitment to “Intended Mission Focus,” whereby fusion centers would need to establish a list of serious violent offenses (including terrorism) that are the exclusive set of issues the facilities focus on.1 Congress could also build this condition into the legislation it passes to fund these grant programs.

Federal agencies could also limit use of data access and information sharing tools to fusion centers that have such a list, such as the Homeland Security Information Network and the Federal Bureau of Investigation Network. Because this involves the federal government choosing how to share or restrict its own resources, it could make use by fusion centers explicitly contingent on those facilities not being used to investigate abortions; such a requirement could be codified through the memorandums of understanding that permit fusion centers to access federal systems and databases.

***

Although they are operated by states, fusion centers would not exist without federal support. If the administration does not want these facilities to contribute to abortion surveillance — especially by broadening the ability of states with bans to monitor individuals’ out-of-state activities — it should take steps to more vigorously condition support for fusion centers on an agreement not to support abortion investigations.

***

1 Fusion centers were established in the aftermath of the September 11th attacks in order to facilitate information sharing for counterterrorism purposes. They were supposed to help law enforcement “connect the dots” to uncover terrorists’ plans. However, their role has morphed far beyond that original goal, and fusion centers are now used for a wide range of law enforcement activities. A majority of them include general crime and narcotics as “top areas of focus” according to the most recent National Network of Fusion Centers’ annual report.