Apple iOS 6 and Privacy

When iOS 6 was released last week, the “big news” was Apple’s decision to drop Google Maps. In the uproar that followed, iOS 6’s privacy features received little fanfare, despite undergoing a major overhaul. Many changes CDT has advocated for—including giving users more control over tracking and increasing the visibility of and options in the privacy settings—have been adopted in the new version.

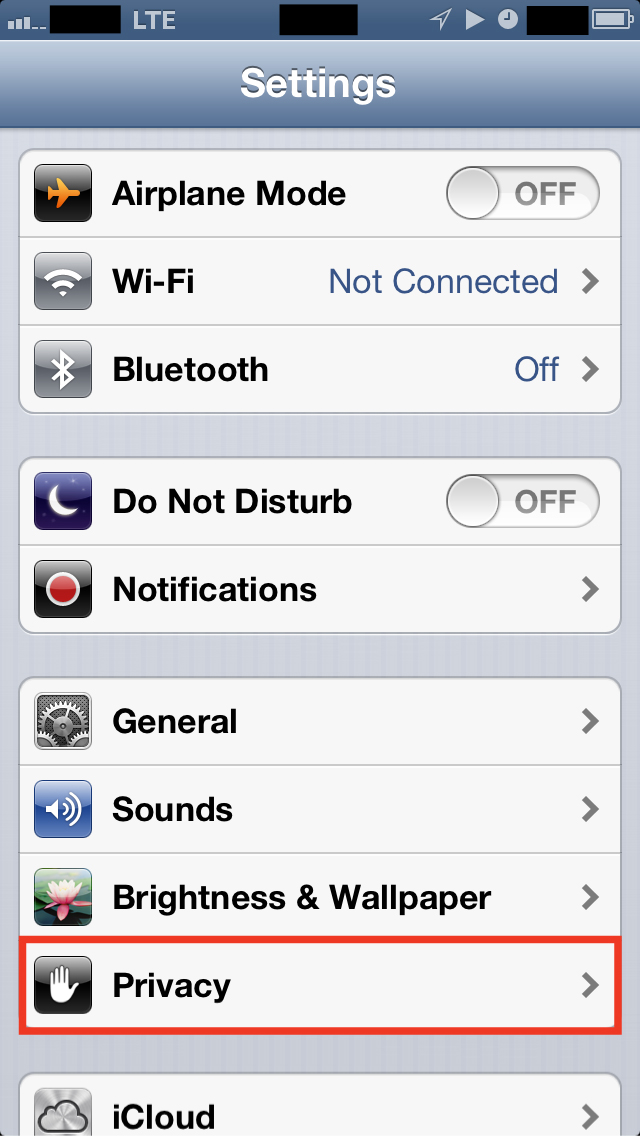

In Settings, Apple has created a new Privacy tab (see the images below). It contains the familiar Location Services tab, allowing users to determine which apps have access to the device’s location. The Privacy tab also lists a number of other types of data that will now require explicit requests to the user for data sharing, including Contacts, Calendars, Reminders, Photos, and Bluetooth. (Android, by contrast, lists all information and services that an app can access during installation, although they can’t be changed later without a manual app update and a permissions notice to the user.)

Apple has also allowed users to limit advertising tracking, via Settings > General > About > Advertising > Limit Ad Tracking. When users enable this setting, they are setting a “flag” that tells apps they don’t want to be tracked, much in the same spirit of the W3C’s Do Not Track efforts. It’s unclear why this setting is located outside of the Privacy settings and deep in the General settings, but its existence and functionality are welcome.

Apple has incorporated three new identifiers to take the place of the much-maligned and unchangeable UDID: iOS 6 now makes available a vendor-specific identifier, identifierForVendor, that can be used by app developers to recognize a device across their apps; a second identifier for advertising purposes, advertisingIdentifier, that can be used by third-party ad networks to identify a device for advertising purposes; and a third application identifier, UUID, that is a more accessible way for applications to create identifiers specific to that application. These three IDs may sound similar but the details are quite different: The vendor identifier is cleared when the user uninstalls the last app on their phone by a given vendor; the advertising identifier persists until the device is completely reset; the application identifier persists only if the application saves it, and then only until that application is uninstalled. Each of these new identifiers is preferable to the UDID, which cannot be modified.

How could these identifiers be used by apps? If a single app needs to store a lightweight device-specific identifier, they would choose the UUID (the UUID is quite different from the UDID; the UUID has a time-based element which means that two UUIDs created at different times will be completely different). If an app provider needs an identifier that persists across each of their apps, they would choose the identifierForVendor, which can be used across all the apps for a given vendor; for example, allowing a family of privacy-sensitive apps like Blendr/Grindr to offer “no personal information required” logins across each app where account information is tied to a device instead of personal information like an email account and name. Finally, for advertising purposes the advertisingIdentifier can be used to deliver, measure, and target advertisements to users. With the advertisingIdentifier, Ad networks installed in apps from different vendors will be able to track users across all the apps on which they are installed on the device – for example, a user’s love of wine in a wine cellar app could be leveraged to offer a discount on wine paraphernalia in a shopping app. This identifier is universal, making it easier for ad networks to trade and sell information about users (compared to the cookie-based model on the web, where each ad network has a different identifier for a user that only it can read). Arguably, Apple should have tried to replicate an advertiser-specific identifier for mobile, or at least made the identifier easier to reset.

However, the “Limit Ad Tracking” setting ameliorates the persistence of the advertisingIdentifier as app developers will have to check if the user has enabled the preference before they read or use the advertisingIdentifier in their code. If “Limit Ad Tracking” is set, advertisers and ad networks are only allowed to use the identifier for a limited set of exempted uses: “frequency capping, conversion events, estimating the number of unique users, security and fraud detection, and debugging.” CDT has long advocated for exactly this balance between user preferences and limited operational uses. This is an important and subtle balance. In negotiating the meaning of “Do Not Track” in the World Wide Web Consortium, we have argued that other uses like “market research” and “product improvement” could tip the scales too far; while these uses don’t directly impact the user’s experience, they wouldn’t be expected by users who enable the Limit Ad Tracking preference and these uses allow data collection of indeterminate scope and extent, potentially acting as exceptions that swallow the rule. The balance struck by Apple here in terms of permitted uses is a careful and appropriate one between honoring users’ desires to limit advertising tracking and ensuring a baseline level of accepted uses that promote a healthy app ecosystem. Furthermore, because Apple must approve iOS apps, they must respect the user’s choice for Limited Ad Tracking or face rejection or removal. This is in sharp contrast to Do Not Track, which requires affirmative representations and agreement from advertising networks to have any weight.

Finally, iOS 6 fixes some 200 critical vulnerabilities across the entire operating system. Some of these vulnerabilities are serious: from allowing bypass of the PIN-enabled lock screen to viewing pictures taken on the device without entering a PIN to running arbitrary code on the device by loading a malicious image file. Unfortunately, iOS 6 is only available for iPhone 3GS and later, iPod Touch 4 or later and iPad 2 or later, meaning the large quantity of older devices will still be subject to many of these potential problems.

CDT applauds Apple’s decision to incorporate these substantial pro-privacy elements into iOS 6, allowing users to finely control how their data gets shared with specific apps, and to more easily express a desire not to be tracked by marketers. We hope that this effort encourages mobile OS vendors to continue to iterate and compete on built-in privacy controls. For years, CDT has periodically published a report comparing the privacy settings for the major browser vendors. We are now in the process of evaluating the major mobile OS platforms in terms of comparative privacy features. Stay tuned!