Cybersecurity & Standards, Privacy & Data

Techsplanations: Part 5, Virtual Private Networks

Previously in this series, we talked about what the internet is and how it works, what the web is, and net neutrality. In this post, we examine the virtual private network, or VPN, a popular and prominent privacy-enhancing tool. We dive deep on what it is, how it works, and then talk about some of the challenges internet users have using VPNs. As before, please refer to this glossary for quick reference to some of the key terms and concepts (in bold).

One increasingly popular and prominent privacy-enhancing tool is the virtual private network, or VPN, which we’re going to explain a bit on this page and talk about some of the challenges internet users have using VPNs.

What is a VPN?

Illustration by Joseph Jerome.

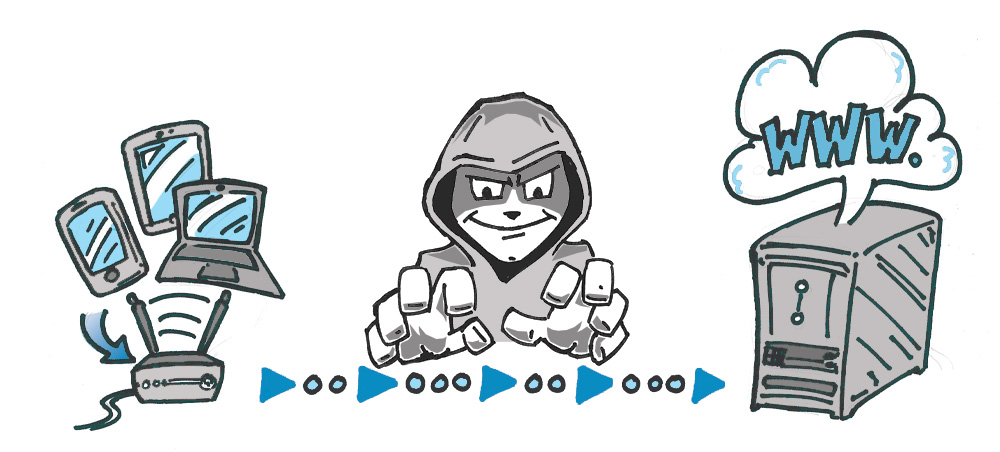

When browsing the internet or connecting “smart” technologies, we leave a trail of information that is valuable to companies, governments, and bad actors. Unsecured Wi-Fi networks are everywhere and easily accessible to anyone with a bit of technical skill who might be curious. A means of shielding oneself from these prying eyes is undoubtedly attractive. A virtual private network, or VPN, creates a virtual tunnel that encrypts and obscures some of this information.

Illustration by Joseph Jerome.

VPNs are a tool that disguises your actual network IP address and encrypts internet traffic between a computer (or phone or any networked “smart” device) and a VPN’s server. A VPN acts as a sort of tunnel for your internet traffic, preventing outsiders from monitoring or modifying your traffic. Traffic in the tunnel is encrypted and sent to your VPN, which makes it much harder for third parties like internet service providers (ISPs) or hackers on public Wi-Fi to snoop on a VPN users’ traffic or execute man-in-the-middle attacks. The traffic then leaves the VPN to its ultimate destination, masking that user’s original IP address. This helps to disguise a user’s physical location for anyone looking at traffic after it leaves the VPN. This offers you more privacy and security, but using a VPN does not make you completely anonymous online: your traffic can still be visible to the operator of the VPN.

It is also important to recognize that a VPN is not the same thing as an ad blocker. It can mask your IP address, but a VPN does not, by default, disrupt other sorts of online tracking. VPNs are not ad blockers or other tools that block efforts to track your activities across websites and devices. The protections offered by a VPN are also not the same as those offered by web browsers, such as private modes that clear cookies on exit or security-focused browsers like Tor. VPNs are generally faster than Tor, but Tor can potentially provide more anonymity.

Why should someone use a VPN?

Why you might use a VPN really depends on your threat model, or what traffic you want to disguise and from whom. Enterprise VPNs have long been used by employers for teleworking or to give remote employees access to employers’ computer networks, but data breaches, government surveillance, and debates about net neutrality have driven additional VPN use by individuals in the United States. For example, when Congress rolled back the FCC’s broadband privacy rules in 2017, VPNs were suggested as one tool to limit the amount of web browsing activities and network information available to ISPs.

While it is true that a trustworthy VPN can shield you from having your ISP see your browsing activities, VPNs provide their best benefits by shielding your activities from other third parties that can monitor traffic on local networks. A VPN is a good tool to have if you do any of the following:

- Look for any unsecured Wi-Fi networks to connect to while traveling.

- Frequently take advantage of Wi-Fi networks at coffee shops or airports.

- Connect to secured networks at hotels or other businesses that monitor internet usage.

Unsecure networks are a big problem; hackers can position themselves between you and the internet access point, or be the access point. This allows complete access to anything you do online. A VPN can protect you from this sort of snooping. However, anywhere a network can be monitored by a curious customer, bad actor, or interested employer can warrant a VPN.

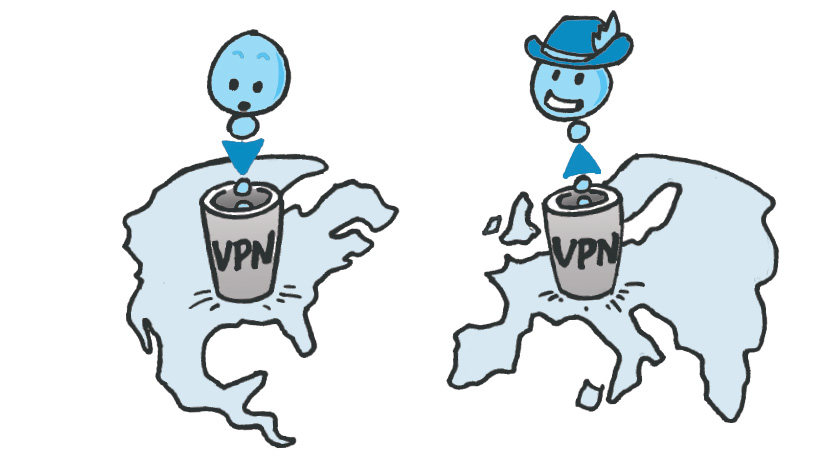

Many people seek out VPNs to access content restricted by geography or to torrent and download media. This is because VPNs can disguise your general physical location by changing the IP address seen by the receiving end of your communications. A VPN hides your true IP address, which reveals your general location and can be valuable to anyone from advertisers to law enforcement, and shows your traffic as coming from an IP address assigned by the VPN. This not only protects your privacy by disassociating your web traffic from your home IP address, but also allows VPNs to effectively “tunnel” your traffic to another country or physical location. In this way, VPNs can help people get around content restrictions, blocked websites, and government censorship. VPNs, for example, have been an important tool to help people in China circumvent internet access restrictions and access sites blacklisted by the government.

How does a VPN work?

VPNs rely on servers, protocols, and encryption to disguise your data. If you’ve been reading this series, you should already know what the internet and the World Wide Web (that lies atop the Internet) are. Web servers receive packets of information from your modem, which has an IP address. This content and metadata can be very revealing. While unencrypted data packets are what users are often most concerned about, even our metadata reveals a lot about us. Every piece of technology your modem interacts with can learn a bit about you, which can reveal a great deal accumulatively, over time.

For example, if I visit a website to see what medical help I can get for a rash or infection, that site will learn my IP address and it will frequently log that information. This information can be used to analyze how many people visit a site or where traffic is coming from; it can also be shared with marketers or law enforcement, who can learn other information attached to that IP address. A VPN essentially replaces this visible metadata.

Illustration by Joseph Jerome.

When you launch your VPN, either as software on your computer or as an app on your phone, your traffic is encrypted and sent to your VPN and then sent onward from your VPN’s servers to your ultimate online destination. Third parties see this information as coming from a VPN server and its location, not your computer or your general location. For example, if I search for the IP address of my computer at CDT, I can learn it is 199.119.118.22, located in Arlington, Virginia. When I turn on one VPN, my IP address changes to 178.128.45.1, based in the United Kingdom. Another defaults to placing me in Los Angeles. A third keeps me close to home in Washington, DC.

This ability for VPNs to make it appear that your traffic is coming from elsewhere is how and why VPNs were used to circumvent online censorship controls, or access movies or digital content that are geoblocked. These sorts of activities can violate the terms or conditions of using those services, and many popular services block IP addresses known to be associated with VPNs. That stated, the number, variety, and location of servers that a VPN offers is often an important selling point. Many VPNs rely on third parties to host their servers, but this comes at the expense of having physical, in-house control over them.

In addition to servers, VPNs rely on protocols to ensure traffic arrives to a VPN server and back. These protocols make up the “tunnel” for your traffic and are a mixture of transmission protocols and encryption standards, which can impact the security or speed of your traffic. Transmission protocols like PPTP, L2TP/IPSec, SSTP, IKEv2, and OpenVPN are instructions for how a VPN makes an encrypted connection. Unfortunately, there is no standard transmission protocol. Each has different pros and cons. CDT recommends that most people use connections based on the OpenVPN protocol. Like HTTPS websites, OpenVPN relies on SSL/TLS. OpenVPN is a widely regarded and, importantly, open source protocol, but it may require additional work to download, install, and configure.

There are different levels of encryption to consider, as well. Encryption is like a lock that protects information. For maximum security, bigger is generally better: AES 256-bit encryption provides a good security baseline. A 256-bit encryption key, for instance, would have 1.1579 × 10^77 different lock combinations. Put another way, if the fastest computer in the world were to start guessing combinations, it could take longer than the entire lifespan of the universe to crack your key.

VPNs use encryption for a number of different purposes. For instance, encryption is used in VPNs both to protect information from anyone monitoring the tunnel and to authenticate that both the user of the VPN and the VPN provider are who they claim to be. The level of encryption really depends on what the security risk is, and a user-friendly VPN will explain what encryption method it employs and what options users have.

Sounds great! What’s the catch?

Despite how VPNs are often marketed, they do not make a person absolutely anonymous online. They only disguise your traffic to some third parties. A VPN will not stop services like Google or Amazon from recognizing you if you sign into their services, and VPNs also cannot stop the types of invasive data fingerprinting or web tracking technologies that are pretty good at guessing who you are without your knowledge or participation. VPNs are just one tool among many to protect your online privacy.

And they are a tool that requires you to trust the provider of the VPN service, which can be easier said than done. Trust, or lack thereof, is a huge problem in the world of VPNs. Even the Federal Trade Commission has basically suggested that “buyer beware” when it comes to researching and choosing a VPN. The need for trust can be eliminated by installing your own VPN such as Algo, JigSaw’s Project Outline, or Streisand, but none of these tools are as easy to install or use as a commercial VPN service. They also require a user to sign up for a cloud service provider like Amazon Web Services to host the VPN server.

These tools have gotten more accessible, but for most users, commercial VPN services are the easier solution. This makes the reputation of the VPN incredibly important. Two years ago, ArsTechnica detailed the struggle to create a list of trustworthy, safe, and secure VPNs, and even today, while there are endless amounts of VPN review sites, it is often unclear how biased or accurate these resources are. That One Privacy Site has become perhaps the most critical source of reviews and comparison information about hundreds of different VPNs, and Wirecutter’s recent exploration into VPNs (which in full disclosure, CDT contributed to) also highlighted privacytool.io as a useful resource for information on VPNs.

CDT has been working with a number of VPNs to promote better practices. You can learn more by visiting CDT’s Signals of Trustworthy VPNs resource page.