From Our Fellows: Envisioning a Healthy Information Ecosystem

By Courtney C. Radsch, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Research Fellow, UCLA School of Law and CDT Non-Residential Fellow

Disclaimer: The views expressed by CDT’s Non-Resident Fellows and any coauthors are their own and do not necessarily reflect the policy, position, or views of CDT.

Fighting disinformation has become one of the leading concerns of governments and donors, spurred the creation of new programs and scholarship, and fueled by new legal regulatory and platform policies. The field of mis- and disinformation has been called too big to fail, despite recognition of the definitional challenges and limitations it has spurred, the lack of scientific knowledge and consensus about effective interventions, its Anglocentric viewpoint that obscures historical, economic, and technological factors including the legacy of imperialism, colonialism, and structural inequality.

But current approaches that encourage a binary logic of accuracy and facticity versus misinformation largely ignore the role of information and communication as cultural practices and the way that we think together and construct meaning collectively. We cannot fact check our way out of polarization, distrust, and skepticism.

So instead of focusing all our energy on how to fight disinformation, mitigate online harms, and combat digital extremism, we need to focus on creating a positive vision of what we want and how to get there.

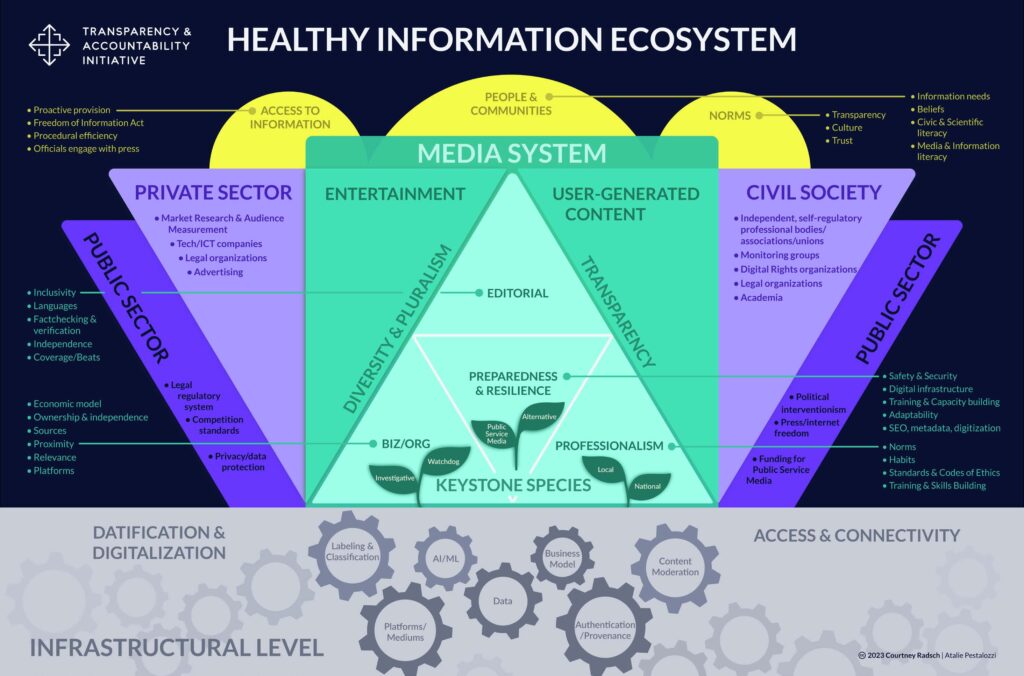

We must cultivate systems, institutions, and norms that enable quality and useful information to flourish and address the interplay between the technological infrastructure in which information and media systems are embedded.

A systems-based approach can improve awareness of resource allocation, where the gaps are, and how different funders and programming interact so that they can design more meaningful and effective objective-oriented interventions and support. Rather than putting the individual, citizen, or community at the center of analysis, this approach focuses on the way that information, technologies, institutions, norms, and practices refract across the larger networks in which humans are embedded.

This is why I designed an analytical tool for the Transparency and Accountability Initiative to visualize the interconnectedness and dependencies between various parts of the information ecosystem to help funders and implementers recalibrate how they think about effective interventions, encouraging a more holistic and strategic approach than just combatting disinformation or improving media and information literacy. It is based on empirical and ethnographic research that included nearly a hundred interviews with journalists, media managers, donors, and civil society, along with a multidisciplinary literature review.[1]

A common framework to understand how different strands of funded programming interrelate and impact each other could provoke public and private donors to think in a more holistic way, contextualize existing investment choices, reframe what they consider impact, and identify funding gaps to prioritize for support could be a game changer for the public. Silos between and even within individual donor institutions mean that we are missing opportunities to assure that investments are mutually reinforcing. Shifting to an ecosystem approach would help shift our focus from combatting a negative to building a positive. This shift would also respond to the call by the special rapporteurs on free expression in their joint declaration on World Press Freedom Day to increase efforts to develop a human rights-based framework for a healthy information ecosystem and coordinated global approaches to rebalancing the power dynamics between independent media and online platforms. This article is also a response to that request and offers an analytical tool to conceptualize how to achieve these goals.

What Does “Healthy” Mean?

A healthy ecosystem is a balanced and resilient system of information creation, exchange, flow, and utilization, meaning that it has the capacity to absorb change, adapt, and transform while maintaining the health of keystone species. The media system is a central focus because most information is intermediated through entertainment, user-generated content, and news media.

The infrastructural layer of an information system affords a common set of conditions and digital resources in conjunction with non-digital resources that shape information flows and nurture the ecosystem when they are in balance. A defining trait of contemporary information infrastructures is platformization, even in low-connectivity environments. Platformization refers to the penetration of digital platforms and their economic, political, and infrastructural logic into information communications ecosystems.

Anchor Institutions and Keystone Species: The Role of Media

Anchor institutions and the keystone species within them are vitally important to ecological survival because without them an ecosystem is likely to become unhealthy in ways that can throw the system out of balance and threaten its survival.

- News media, for example, are anchor institutions that shape the flow and distribution of information and promote transparency and accountability by holding those in power accountable. The human, material, and political dynamics affecting the health of these institutions have a particularly strong effect on the resiliency of factual information in the broader system.

- Public interest news media are keystone species, and when optimally healthy reflect the diversity and pluralism of the locality in which they are embedded. Without public interest media, democracy withers, corruption flourishes, and authoritarianism proliferates.

Diversity and pluralism, along with transparency, are characteristics of healthy systems and keystone species alike. Transparency cultivates trust among components of the system and with the humans involved. For example, editorial or ownership transparency is interrelated with trust (cultivating), and political interference (mitigating).

Integrity and Infrastructure: Linking Technology and Information Flows

Contemporary information ecosystems are constructed on digital infrastructures that include the platforms from prior eras, like broadcast and print, but also new ones that are distinctly generative, adaptive, and networked.

In my recent work, I have explored how platformization impacts media sustainability, from shaping the editorial and economic logic of the media and advertising industries to facilitating the spread of propaganda and influence operations. Content moderation and labeling affect visibility and monetization, while public policy, transnational legal regulatory frameworks, and language shape moderation practices. How tech platforms allocate resources to AI research and development and foundational training models, for example, can facilitate or impede the accuracy of content moderation, the spread of propaganda, and the prevalence of harassment, and thus impact the health of the information ecosystem more broadly because of the interrelatedness.

The concept of infrastructure is important because infrastructures are ubiquitous and thus generate dependency and habituation within an ecosystem. Information providers, for example, are dependent on platforms for access to their networks, audiences, data, publishing protocols, advertising revenue, and funding, a dependency that influences editorial, organizational, and business choices in the media system. This means considering how characteristics and developments in this technological infrastructure affect keystone species, like news media.

Healthy information ecosystems support diverse and pluralistic sources of information and must find ways to ensure information integrity, both in terms of provenance and authenticity as well as responsible information production, management, and securitization practices. For example, when information that cannot be verified floods the system, or poor digital security practices enable hacking and impersonation, the integrity of information becomes suspect and can have all sorts of pernicious ramifications. As generative AI promises to exponentially increase the amount of content created, the ability to detect and authenticate provenance will become increasingly important even as it becomes drastically more difficult.

Fact-checking is only going to get exponentially harder as generative AI promises to turbocharge the amount of manipulated content and deep fakes in circulation which enhances the importance of information integrity and trust initiatives. Journalists will need to have access to digital forensics expertise, special skills, and technology to detect and determine provenance and authenticity. But they also need technological solutions. Are donors going to strategically support this work?

Fact-checking has emerged as a key funding priority and has given rise to hundreds of media and fact-checking organizations with 431 active fact-checking projects in 102 countries, according to the International Fact Checking Network. Yet little has been done to remodel the infrastructure through which disinformation proliferates. Coordination and application of fact-checking efforts have been limited, meaning that journalists are left to clean up disinformation one article, image, and video at a time, often just to see it pop up again on another site, messaging app, or another language. There is limited hashing or coordination of cross-platform or multilingual moderation of fact-checked content, and no powerful shared databases that could help fact-checking even begin to address the scale and scope of disinformation.

The penetration of digital platforms and their economic, political, and infrastructural logic into the web and app ecosystems, fundamentally affects the health of the ecosystem. In the news media system, for example, digital advertising and the platform logic of engagement and content moderation fundamentally shape the economic model for sustainability, editorial priorities, and professional skill sets.

Cultivating an Enabling Environment: The Roles of the Public and Private Sectors

To this end, the role of the public and private sectors is important to factor in. Regulatory and policy interventions, for example, shape the balance of power between different players in the ecosystem and the rules they must play by. Policies like Australia’s News Media Bargaining Code and other efforts to make Big Tech pay for the news it uses are aimed at rebalancing this power dynamic to improve the health of the news media because of the crucial role it plays in the information ecosystem of democracies. Regulatory efforts like the Digital Services Act and UK Online Safety Bill seek to bring greater transparency to some key components of the infrastructure layer, like content moderation and other algorithmic systems but could threaten others, like encryption.

AI and content moderation systems shape information production, flows, and voids. These resources and information flows also affect the keystone species and other elements of the information ecosystem, meaning that when they get out of balance, they can impact the health and resiliency of seemingly unconnected elements in the media system as well as the broader information ecosystem. For example, content moderation affects the visibility and viability of all types of digital media, from user-generated content to science and journalism.

Information ecosystems are profoundly influenced by research and development choices by civil society actors in academia and the private sector, but to what extent are donors considering this in their strategies? These choices impact the resources devoted to Natural Language Processing (NLP), object recognition, and other types of machine learning, and the ways in which data is collected and organized. They are driven by datafication, privacy and data protection rules, and platform business models. This is why, for example, Meta devotes the vast majority of its content moderation resources to English and ignored recommendations from its own research about how to make Facebook healthier.

Threat-based funding and interventions are largely focused on individualistic interpretations, which isolate individuals from the broader environment. It assumes that humans control their environment and “think alone as rational individuals” rather than consider how they collectively create and are situated within it; it also ignores the broader technological infrastructures that shape information creation, flows, and reception. In contrast, ecosystem analysis generates a positive vision for nourishing a thriving information system that goes beyond fighting disinformation and individual resilience to root causes and interrelated dynamics.

By addressing imbalances, interdependency, and the role of keystone species, the donor community and practitioners can identify areas for strategic reallocation and investment. We must create the conditions for a future where accurate and diverse information is readily available, and individuals can make informed decisions that benefit themselves and society as a whole. It’s time to invest in a healthy information ecosystem.

[1] The production of this visual and analysis was funded by the Transparency and Accountability Initiative and designed in collaboration with Atalie Pestalozzi. The author received support for research that informed the analysis from the UCLA Institute for Technology, Law & Policy, Internews, the Center for International Governance Innovation, the Center for International Media Assistance, and the Global Forum for Media Development. Thank you to Alessia Zornetta for initial research assistance.