Facebook Responds to User Demands for Control

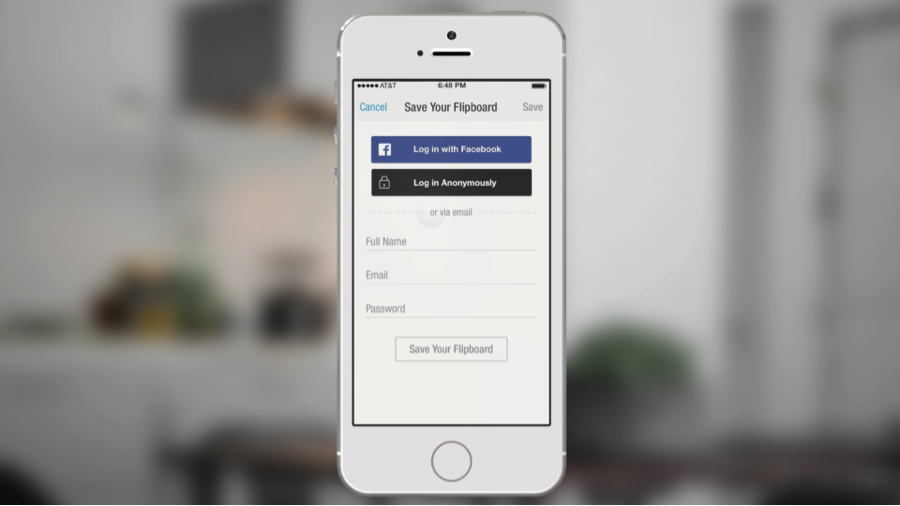

Earlier today Facebook* announced Anonymous Login — a way to use Facebook to log into third-party apps and services without sharing your personal Facebook information with those apps and services. It’s no secret that people are increasingly worried about their online privacy, so it’s heartening to see companies respond with new tools to limit the dissemination of their personal information.

The Internet has always been of two minds about Facebook Login. Some love it because it allows you to seamlessly create new accounts without remembering dozens of different usernames and passwords with varying requirements (Wait, is this the site that requires a capital letter and a punctuation mark? Damn, two more tries before they lock me out). Others hate the idea of apps rummaging through their contact lists and other personal information, , or they simply don’t want to give Facebook more information about what they do with other companies.

Personally, I’ve never used Facebook Login because I don’t want to give sites access to the rather personal information I choose to share on Facebook. Of course, the alternative is often to provide an email address — an identifier that the service could search on a data broker’s site to find out who I am and quite possibly more. Given those two options, I’m willing to give Anonymous Login a try.

To be clear, “anonymous” isn’t exactly the right word. “Anonymous Login” is arguably a contradiction in terms — the term login signifies someone keeping identifiable information on you and keeping track of your status over time. Facebook Anonymous Login just means that a site will get a unique identifier for you from Facebook whenever you use the service and that identifier cannot be tied back to your Facebook profile unless you later choose to do so. This way, you can use Facebook to login to the service from different computers at different times and the service will know you’re the same person — but that’s all the site gets. They don’t know your name, your email, or anything else about you (unless they ask and you tell them). “Pseudonymous Login” is probably a more accurate (if clunky) term in that they are replacing the real information about you — your Facebook profile information and Facebook ID number — with a unique UD that can only be used with that app or service.

Facebook will have to be clear with users that this doesn’t solve all app privacy issues. Facebook itself will still keep track of the services you use it to log in with, so if you don’t want Facebook to know what other sites you have accounts with, you shouldn’t use any Facebook login service. (Facebook should also be a bit more clear in its privacy policy and FAQs that while it knows which services you login to using Facebook, they don’t know what you do on those services.) Moreover, if Facebook receives legal process requiring it to reveal the identity of a certain site user that uses Anonymous Login, it would be able to comply and reveal who you are.

If you really want to limit what apps — and Facebook — can collect about you, you should probably use the Tor Browser and a password and account management service that generates unique account names, email addresses, and passwords for every different service that you use. Of course, even then, you need to be able to trust the software or cloud service provider that you use to manage all that information.

However, if your primary concern is that you want to limit what websites and apps collect about you — or the hassle of using more sophisticated privacy-preserving tools isn’t worth it to you — Anonymous Login is a positive development. Developers won’t be required to offer this option to users (they can stick with the existing Facebook Login) but hopefully many will see the benefits that come with increased user trust. Today, a lot of users balk at the myriad permissions that apps request when presenting Facebook Login as an option; one app developer notes that 21% of users hit cancel when they see the permission screen. Hopefully the prospect of increased engagement will encourage sites to let people use their services anonymously (pseudonymously, whatever).

In general, I see Anonymous Login as part of an encouraging trend in the privacy world. Increasingly, companies (at least some) are recognizing that limiting data collection is vital for user trust. A couple of years ago, Facebook was telling the world that everything needed to be social. Now, faced with user backlash and competition that supports pseudonymous and ephemeral sharing (like Tumblr and Wickr), it’s offering tools to give you better control over your personal information. Some have argued that the era of Big Data means that user control should play a lesser role in privacy protection — that because there’s so much more data out there about us, we can’t be expected to manage it anymore. This perspective has it backwards — more data means that there should be stronger controls, not weaker ones. The canard that young people don’t care about privacy has already been exposed. More companies are going to have to recognize that consumers aren’t willing to throw up their hands and accept the digital panopticon, and that people need better ways to manage how their personal information is exposed. Tools like Anonymous Login are a step in the right direction.

[*Disclaimer: Facebook provides some funding to CDT. The views represented here are our own and not Facebook’s.]