Exploring Inclusive Language Adoption in Internet Standards

This post is authored by Summer 2023 CDT Intern Lauren Chambers

As the internet has grown to affect more and more aspects of our lives, something has remained the same: the vast majority of internet users don’t understand how it works. HTTPS, DNS, TLDs, QUIC, IPv6 — the nuts and bolts of internet standards are Greek to most of us.

Thankfully, there are thousands of people working together and taking great care to maintain the seamless functioning of the internet within standards-developing organizations (SDOs) such as the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). The decisions that these organizations make affect the fundamental infrastructure of our internet.

As an intern with CDT’s Open Internet team this summer, I set out to better understand the history and adoption of inclusive terminology in internet standards. To conduct this analysis, I learned to use an open-source software toolkit for scientific analysis of SDOs – called BigBang – to access public SDO email mailing list data.

Here I share my experience using this software to explore the characteristics of SDOs, and document what makes BigBang such a unique and powerful tool for understanding how the internet is built and maintained.

Inclusive Language in Internet Standards

In 2018, Mallory Knodel, now the CTO at CDT, published an “internet draft” (a document offered up for broader IETF discussion) addressing “Terminology, Power and Oppressive Language.” In it, Knodel and her co-author Niels ten Oever called on the IETF community to reflect on the ways that certain terms commonly used in technical contexts might have discriminatory origins or unintended consequences.

Specifically, the authors cautioned against the “racist and race-based meanings” couched within the technical terms “whitelist” and “blacklist,” as well as “master” and “slave” (terms that refer to asymmetrical dynamics of control in computing).

Discussions about inclusion and oppression became only more passionate in the summer of 2020, when the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor sparked international protest and unprecedented conversation about the realities of racism and injustice within even niche technical communities.

Though Knodel and ten Oever’s draft caused a stir, it was one among a large chorus of calls for discussions taking place across the tech sector about the cultural implications of computing terminology. Indeed, in recent years Google, Python, Linux, Apple, and GitHub have all publicly announced policy changes to move away from such language.

And discussions are still ongoing — the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Standards Association (IEEE SA) is soon to issue a ballot that would adopt “inclusive and inoffensive” terminology across the standards association, touching a range of technical domains. What’s more, the Inclusive Naming Initiative brings together leaders from across the technology sector to discuss and offer recommendations to “replacing harmful and exclusionary language in information technology,” and is launching its official language guidance soon.

What We Found

So, how has usage of exclusive terminology within SDOs changed over the past decades?

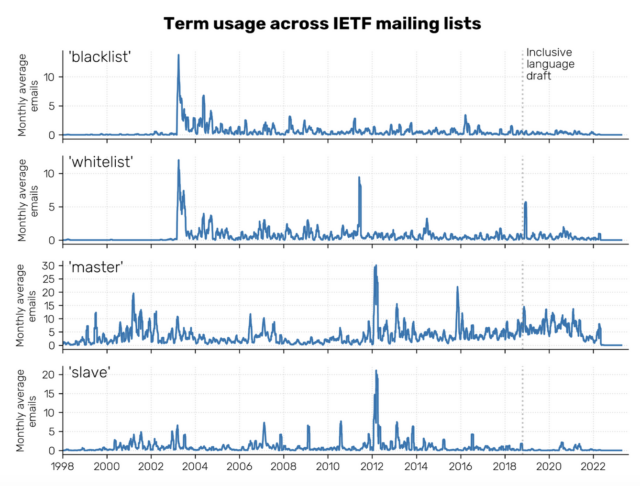

Using BigBang, we were able to trace the usage of four terms — blacklist, whitelist, master, and slave — on IETF mailing lists since the late 1990s. Our analysis includes data from approximately 1,100 mailing lists through 2022 (as the toolkit hasn’t yet been updated to parse emails from more recent years).

This analysis does not count automated emails from GitHub, which often included mention of the reference “refs/heads/master,” nor does it count text copied below email replies, to avoid overcounting terms that appeared and re-appeared in long email threads.

The Jupyter notebook we used to conduct this analysis is available on GitHub.

The data show that usage of these terms has changed over the past two decades, decreasing in recent years. The use of the terms “blacklist” and “whitelist” has declined sharply since the early 2000s. While the term “master” has been used more consistently over this timeframe, its usage has dropped since 2020. Finally, we see that the term “slave” is barely used in IETF correspondence nowadays.

Though not across the board, we also see a direct uptick in email chatter using the terms “whitelist” and “master” after the 2018 publication of Mallory and Niels’ draft proposing more inclusive terminology. Using BigBang, we were able to identify specific conversations – for instance, emails from November 28, 2018 document the DDoS Open Threat Signaling (dots) working group as they discuss the adoption of “accept-list” and “drop-list” as alternative terms to “whitelist” and “blacklist.”

Thinking Big with BigBang

While this summer’s project was exciting, it’s just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to what you can do with BigBang.

Presentations at an IETF conference in early 2023 demonstrated how BigBang data can be combined with sophisticated analytic methods to apply to many innovative tasks. These range from providing data-driven suggestions regarding who is well-poised to review IETF standards drafts, to extracting deeper insights from email data by using entity recognition with large language models. The software package was even used in a PhD dissertation studying standard-setting communities written by CDT’s own Nick Doty.

Further, while the BigBang package is maintained by developers in the IETF’s Research and Analysis of Standard-Setting Processes Research Group (or RASPRG), it also provides interfaces to process mailing list data from other standards-setting bodies, including:

- The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C),

- The 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP),

- The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), and

- The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN).

Solely regarding questions of inclusion and representation, additional BigBang projects that we brainstormed at CDT but didn’t get to this summer include:

- What is the affiliation of participants in IETF mailing lists, authors on internet drafts and Requests for Comment (RFCs), and attendance at IETF meetings? How many are based in industry, academia, civil society?

- What is the gender breakdown of IETF meeting attendance and participation in emails/drafts/RFCs?

- How does IETF meeting attendance and participation in emails/drafts/RFCs break down by geographic region?

- In all of these, how does IETF compare to other SDOs?

Try It Yourself

Anyone who wants to try their hand at this sort of analysis can check out the BigBang software package on GitHub. Installing and using the package requires some familiarity with the command line, virtual environment management, and coding in Python.

Interested users should also know that it takes significant time and hard drive space to download mailing list datasets. For instance, downloading all of the IETF mailing list data took a couple nights of background runtime, and over 40 GB of space — using an external harddrive is a great idea).