Privacy Groups Say 221 Days of Location Tracking Requires Warrant

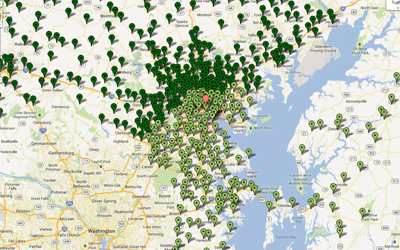

Map of Sprint/Nextel cell sites in the Baltimore area

Yesterday, CDT, EFF, and NACDL signed onto an American Civil Liberties Union amicus brief in U.S. v. Graham arguing that law enforcement’s access to 221 days of stored cell site location information requires a warrant.

In the amicus brief we demonstrate the ease with which the government can connect the dots of the Defendant’s movement to illustrate telling patterns of behavior, such as when a Defendant, Mr. Graham, accompanied his pregnant wife to the OB/GYN’s office, when he spent the night at home, and where he spent the night when a few miles away from home. With 221 days’ worth of data encompassing 15,000 phone calls, all of this can be surmised from historical cell site location information, and the government got it all without a warrant.

The government invokes the Third Party Doctrine – i.e. information that a customer shares voluntarily with a service provider like a phone company is not private simply because it was shared with a third party – to argue historical cell site location records can be obtained without a warrant. However, customers are not even aware that companies collect their location data when they make or receive a cell phone call or text message; there is no affirmative submission of location information from the customer to the provider, as it happens automatically. We argue that the only judicial opinion specifically addressing this issue, from the Third Circuit, correctly concludes that users have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their cell site location records even when a provider maintains the records.

Cell phones accompany us wherever we go, whether we’re traveling on public roads or visiting private spaces. When surveillance enables the government to infer whether the phone (and the person holding it) is in a private space – inside a home, or a doctor’s office – collecting location information without a warrant violates the Fourth Amendment.

Quoting Justice Alito, “society’s expectation has been that law enforcement agents and others would not . . . secretly monitor and catalogue every single movement of an individual’s car for a very long period,” U.S. v. Jones, 132 S. Ct. 945, 964 (2012) (Alito, J.). This was true in Jones with 28 days of location information, and this should still hold with Graham’s 221 days of cell phone location information.

The argument that cell site location information is not precisely resolved to the extent necessary to determine location in a privacy-infringing way is disingenuous. In U.S. v. Graham, law enforcement officials resolutely made their case linking the Defendants to the crime scene with just 13 location data points. But the government claimed that the remaining 58,056 data points couldn’t possibly lead to privacy-infringing conclusions. The data is touted as justification for conviction with the same breath that shrugs it off as inconsequential. The government can’t have it both ways.

Finally, we argue that the ubiquity of cell phones coupled with the increasing reliance on cell site location information by law enforcement imbues this issue with a critically important urgency. This urgency makes it clear that courts should step in with protective decisions, and Congress should enact protective legislation to ensure the privacy of location information.