Cybersecurity & Standards, Government Surveillance

The NSA Shuttered the Call Detail Records Program. So Too Must Congress.

On August 14, the White House issued a letter urging Congress to permanently reauthorize expiring provisions of the USA PATRIOT Act (Patriot Act), including the provision that authorizes the mass collection of telephone call records. There is overwhelming evidence, though, that this program has been operated unlawfully and collects hundreds of millions of phone call records every year, and a lack of evidence that it has thwarted even one terrorist attack. It was even shuttered by the National Security Agency (NSA). Congress should reject the White House’s request, eliminate the statutory authorization for the Call Detail Records program, and enact substantial reforms to other intelligence authorities.

In 2015, Congress passed the USA FREEDOM Act to reform Section 215 of the Patriot Act and prohibit the nationwide bulk collection of telephony metadata. The NSA’s program was replaced with a more narrow Call Detail Records (CDR) program to ensure that surveillance was targeted. Or so it was generally believed, and so we believed when CDT supported the USA Freedom Act. Transparency reporting in the intervening years revealed that the NSA still collects hundreds of millions of telephone communications metadata every year, prompting concerns that bulk collection is not yet functionally outlawed. In the next few months, Congress will reassess the CDR program, the rest of Section 215, and two other surveillance authorities that sunset on December 15, 2019. The Center for Democracy & Technology and 36 other organizations urged Congress to enact meaningful reforms as a part of any reauthorization. One such necessary—but not sufficient—reform is removing statutory authorization for the CDR program.

How Does the Program Work?

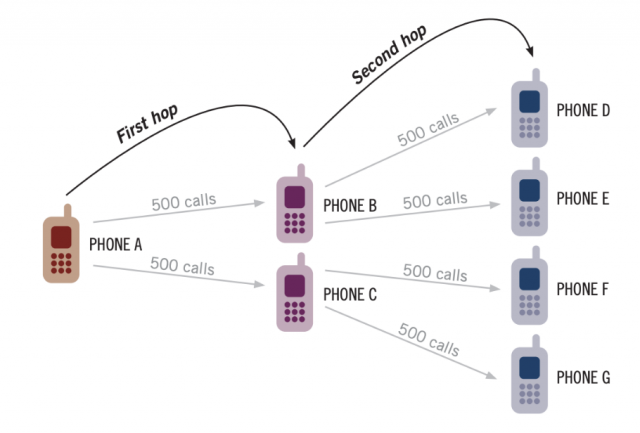

Call detail records are the metadata of telecommunication exchanges like phone calls and text messages, including who is communicating with whom, when, and the duration of the exchange. The CDR program permits the government to request this metadata from telecommunications companies on an ongoing basis. To receive these records from providers, the government must make a number of showings to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC). There must be an international terrorism investigation, and the government must identify a specific selection term (SST) as the basis for the collection of CDRs. An SST must be “a term that specifically identifies an individual, account, or personal device.” The government must also establish to the satisfaction of the FISC that there is a “reasonable, articulable suspicion” (RAS) that an SST is associated with a foreign power or an agent of a foreign power engaged in international terrorism. And there must be reasonable grounds to believe that the CDRs to be produced are relevant to the investigation. If the FISC affirms these findings, it issues a production order that is good for 180 days. The government may also collect records “two hops” away from the RAS-supported SST. The below image demonstrates how this works.

[image from p. 29 of ODNI’s 2019 Statistical Transparency Report]

The CDR program permits the NSA to collect and review the records of those not suspected of any wrongdoing, and of those who haven’t even contacted such a suspect. By the very design of the program, the vast majority of the records are collected from people who haven’t contacted a target. And lest we forget, these records can be very revealing over time. From communications metadata, one can discern patterns of associations and intimate personal details such as relationships or sensitive medical needs. This is clearly a privacy-invasive program. Here are four additional reasons for Congress to kill the CDR program:

The CDR Program Permits Collection of Massive Amounts of Personal Information

When civil society and Congress applauded the passage of the USA FREEDOM Act, it was in part because the reforms to Section 215 were thought to be sufficient to end the bulk collection of domestic phone records. In fact, President Obama praised the legislation’s passage for “prohibiting bulk collection through the use of Section 215, FISA pen registers, and National Security Letters.” However, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence’s 2018 Statistical Transparency Report revealed that in 2017 there were 40 targets for orders to obtain CDRs which enabled the NSA to collect 534,396,285 call records. The 2019 report revealed that, in calendar year 2018, the NSA collected 434,238,543 call records based on only 11 targets. While there is some duplication of records, it is astonishing that the NSA is collecting so many records every year, far more than ever predicted, and based on so few targets. The program is far too sweeping in its scope. This is not the balance between privacy and security that was bargained for.

The CDR Program Has Not Been Operated Lawfully

The USA FREEDOM Act moved the haystack of data away from the NSA and left it in the hands of telecommunications providers. In the CDR program, it is the companies that query their holdings for responsive records based on the government-provided seed number. Such a shift was a significant win—who possesses records can easily end up being nine-tenths of the law. However, the arrangement has had serious hiccups. In June 2018, the NSA announced that technical problems caused it to acquire information it was not legally authorized to possess. Consequently, the agency voluntarily deleted all the call detail records acquired through the CDR program since it began in 2015. The NSA claimed at the time that the “root cause of the problem has since been addressed for future CDR acquisitions”. However, in October 2018, the NSA again received data it was not lawfully authorized to access. The NSA stated that the problems stemmed from “the unique complexities of using company-generated business records for intelligence purposes.” These “compliance incidents” mean that the NSA has collected records of phone calls unlawfully, without disclosing the quantity to the public, or providing enough information to give the public confidence that the program can be operated lawfully.

The CDR Program Is Not Necessary to Stop Terrorism

In the four years it has been operated, the government has not connected the CDR program to a foiled terrorism plot. Back in 2013, the government likewise failed to demonstrate the necessity of the Section 215 bulk collection program, initially claiming that the NSA programs disclosed by Edward Snowden disrupted 54 terrorist plots. Congress and the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB) were able to debunk this assertion. In its seminal Section 215 report, the PCLOB observed that “we have not identified a single instance involving a threat to the United States in which the program made a concrete difference in the outcome of a counterterrorism investigation. Moreover, we are aware of no instance in which the program directly contributed to the discovery of a previously unknown terrorist plot or the disruption of a terrorist attack.”

Rather than rely on the CDR program, the NSA quietly shut it down for several months. A senior aide connected the shuttering with the technical irregularities that prompted the NSA to delete its data holdings in 2018. The NSA reportedly recommended that the program be dropped due to the logistical and legal burdens associated with keeping it running. Even in the administration’s call to reauthorize the program, it officially confirmed for the first time the NSA suspended the CDR program “after balancing the program’s relative intelligence value, associated costs, and compliance and data integrity concerns.” That the NSA could comfortably delete all of the program’s data holdings and shut it down demonstrates that it is nonvital. In the absence of any demonstration of necessity or effectiveness, the balance easily favors privacy. The CDR program must come to an end.

Other Authorities Permit the Targeted Collection of CDRs

Removing the statutory authorization for the CDR program would not end the NSA’s ability to determine with whom a suspected terrorist is communicating. Instead, it would channel inquiries designed to reveal such information toward more targeted surveillance authorities.

The government would still have the ability to compel the disclosure of stored call detail records using a “traditional” Section 215 order. These orders, issued in secret by the FISC, can require an entity to disclose “tangible things (including books, records, papers, documents and other items, including call detail records).” The government must identify an SST as the basis for its application for an order—a telephone number, for example—and must present sufficient facts to demonstrate “reasonable grounds” to believe the “tangible things” requested are “relevant” to an international terrorism, counter-espionage, or foreign intelligence investigation. This is an even broader authority than in the CDR program, which requires a reasonable articulable suspicion that the SST pertains to an agent of a foreign power engaged in international terrorism, so any SST that could be targeted under the CDR program could be the target of a traditional Section 215 order. Unlike the CDR program, the government would only receive one hop of data, not two.

The government could also use the Pen Register and Trap and Trace (PR/TR) authority to capture telephony metadata on a prospective basis. To get a PR/TR order, the government must submit an application to the FISC that identifies an SST, and it must certify that the device will capture information “likely” to be “foreign intelligence information” or information that is “relevant to an ongoing investigation to protect against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities.” Such a method would be more targeted than CDRs as, again, the government would only capture one hop of data, not two.

٭٭٭

Of the surveillance reforms Congress must enact this year, shuttering the Call Detail Records program is low-hanging fruit. Faced with evidence that this program is invasive, ineffective, and operated unlawfully, we expect Congress to agree that this is an easy call. The Ending Mass Collection of Americans’ Phone Records Act of 2019 (S. 936/H.R. 1942), introduced by Senators Ron Wyden (D-Ore) and Rand Paul (R-Ky), and Representatives Justin Amash (I-Mich) and Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif), would strike the authorizing language for the program from Section 215. CDT supports this legislation and believes that the authorization must be stripped from statute. This way, if the NSA decides the CDR program is needed and can be operated lawfully, it will have to persuade a subsequent Congress. This ensures a robust debate on the merits of such a program, and its risks to privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties.

Congress must address other much needed reforms to the sunsetting authorities. But today, we implore Congress to finish the work of the USA FREEDOM Act, and to pull the plug on the CDR program once and for all.