Free Expression, Open Internet

Fair Use in Art, Politics, and Babies Going Crazy

The Center for Democracy & Technology spends a lot of time working on the role of copyright doctrines, like fair use, in enabling new innovations or innovative uses of existing works. The Supreme Court’s Sony v. Universal decision established the central role of fair use in the creation of new technologies that empower users to choose where, when, and how they engage with content. (By the way: at a time when a lot of us are thinking about the influence that individual justices have over the evolution of law, we recommend Jonathan Band and Andrew MacLaughlin’s article, The Marshall Papers: A Peek Behind the Scenes at the Making of Sony v. Universal.) But this blog post is not about that. It’s about the role of fair use in the creation of the content itself, particularly content that reflects on, critiques, or mocks mercilessly the individuals, organizations, or trends that drive political and cultural discourse.

Fair use balances the monopoly of copyright with the public interest in using protected works to learn, create, and express. Copyright gives authors exclusive control over the reproduction, distribution, performance and display of their works. But without fair use, incorporating even the smallest portion of a protected work into your latest creative project would require first obtaining permission from the copyright holder, or risking liability for infringement.

Fair use began as a judge-made law, eventually codified as section 107 of the 1976 Copyright Act. This provision kept the doctrine’s original four-part balancing test, which requires consideration of the purpose and character of the use, the nature of the copyrighted work, the amount and substantiality of the work used, and the effect of the use on the market for the copyrighted work. Each of these factors may weigh, with varying degrees of strength, for or against fair use. Often, whether and to what degree a use is “transformative” (uses the work in a different way than the original) will carry the most weight. Despite the potential for disparate and fact-dependent outcomes, the fair-use test has been applied consistently enough to give guidance to both rightsholders and would-be fair users. Surveys of fair use case law, such as the Copyright Office’s Fair Use Index or Stanford’s Copyright and Fair Use page, show the range of circumstances in which courts have applied the doctrine.

Fair use began as a judge-made law, eventually codified as section 107 of the 1976 Copyright Act. This provision kept the doctrine’s original four-part balancing test, which requires consideration of the purpose and character of the use, the nature of the copyrighted work, the amount and substantiality of the work used, and the effect of the use on the market for the copyrighted work. Each of these factors may weigh, with varying degrees of strength, for or against fair use. Often, whether and to what degree a use is “transformative” (uses the work in a different way than the original) will carry the most weight. Despite the potential for disparate and fact-dependent outcomes, the fair-use test has been applied consistently enough to give guidance to both rightsholders and would-be fair users. Surveys of fair use case law, such as the Copyright Office’s Fair Use Index or Stanford’s Copyright and Fair Use page, show the range of circumstances in which courts have applied the doctrine.

Fair use enables works that comments on or parodies pre-existing ones. In Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., the Supreme Court held that fair use protected 2 Live Crew’s parodic remake of Roy Orbison’s “Oh, Pretty Woman” in which the owners of the copyright for the song “Oh, Pretty Woman” sued 2 Live Crew for their use of portions of the song in a parodic remake (see the case appendices for the lyrics to the Orbison’s original and 2 Live Crew’s sendup. The Court found that, although 2 Live Crew’s use was commercial, it was also sufficiently transformative that it would not damage the market for the original, thus highlighting the relationship between the first and fourth factors.

Fair use takes on special significance in cases that involve the intersection of art, commerce, and politics. In Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Moral Majority, Larry Flynt sued Jerry Falwell for copying and distributing (as part of a fundraising campaign to support his defamation suit against Flynt) more than 1.2 million copies of Hustler’s parodic Campari advertisement depicting Falwell alongside a fictitious description of an incestuous encounter in an outhouse. Even though Falwell copied the entire work and used it for commercial purposes, the court found this use to be fair because it would not affect the market for back issues of the magazine containing the original work. And, of course, the original work at issue in that case itself relied in part on fair use to parody the Campari ad.

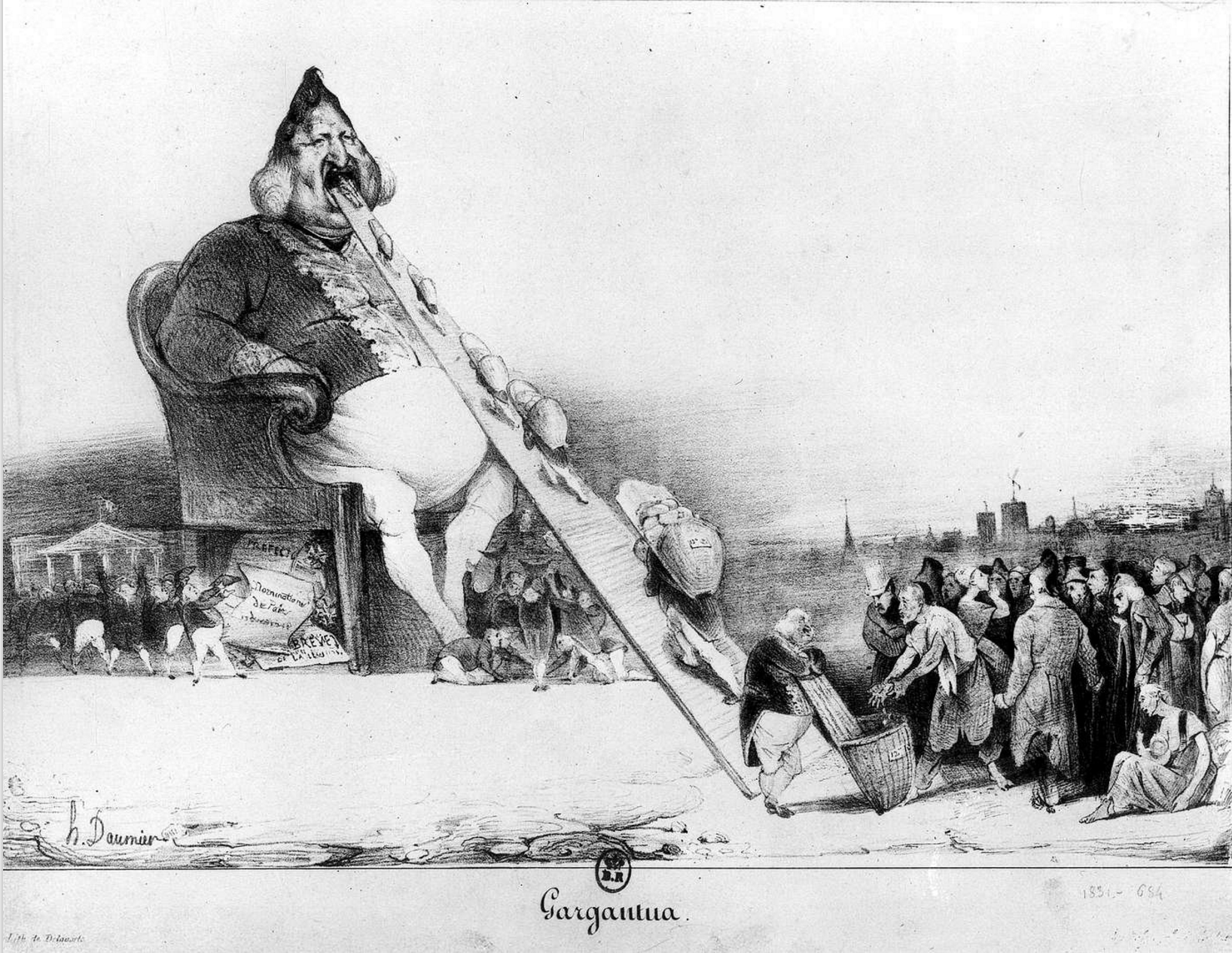

Cases of first impression come up all the time but the repurposing and invocation of original works for political and cultural commentary is not new. It goes back centuries. When, Honoré Daumier, a political cartoonist in 19th century Paris, sought to protest King Louis-Philippe’s limitations on freedom of the press, he invoked the giant Gargantua from Rabelais’ 16th-century novels. As former CDT intern Gray Leonard explains, Louis-Philippe was unamused.

Digital media and the Internet have expanded the ways in which we can borrow, transform, and share creative works, making the iterative process of innovation more rapid and more granular. This year, CDT revamped its Online Art Rights project, which provides an overview of the issues artists and others may face when creating or expressing online and the legal risks associated with those issues. Fair use, part of the fulcrum in the balance between free expression and copyright, features prominently among those issues.

Fair use of protected works, and efforts to suppress works that rely on fair use, comes up a lot in political campaigns. In 2010, CDT published a report (PDF) on abuse of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act’s (DMCA) notice-and-takedown provisions to stifle political speech protected by fair use. In many cases, campaign ads (often hosted on YouTube) incorporated short clips from news programs featuring candidates. The copyright holders for those snippets would send takedown requests to websites hosting the videos, requiring them to either take down the video or risk liability for copyright infringement. The report found that although every instance would have almost certainly been considered a fair use, many videos were removed to avoid risking liability. In a strange twist on political takedowns, the Sanders campaign recently asked the Wikimedia Foundation to remove its own campaign logos from Wikimedia Commons.

Fair use of protected works, and efforts to suppress works that rely on fair use, comes up a lot in political campaigns. In 2010, CDT published a report (PDF) on abuse of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act’s (DMCA) notice-and-takedown provisions to stifle political speech protected by fair use. In many cases, campaign ads (often hosted on YouTube) incorporated short clips from news programs featuring candidates. The copyright holders for those snippets would send takedown requests to websites hosting the videos, requiring them to either take down the video or risk liability for copyright infringement. The report found that although every instance would have almost certainly been considered a fair use, many videos were removed to avoid risking liability. In a strange twist on political takedowns, the Sanders campaign recently asked the Wikimedia Foundation to remove its own campaign logos from Wikimedia Commons.

Last year saw a positive development in the incorporation of fair use protections into the DMCA’s notice-and-takedown regime, thanks to the dedicated folks at The Electronic Frontier Foundation and a dancing baby. In 2007, Stephanie Lenz posted on YouTube a 29-second video of her child dancing in her kitchen while Prince’s “Let’s Go Crazy” played in the background. Universal Records sent YouTube a takedown request, claiming infringement. EFF took up Lenz’s case, asserting fair use and, eventually, the courts agreed (opinion). Now, in the 9th Circuit, copyright holders must at least consider whether a fair use applies before sending a takedown request.

Last year saw a positive development in the incorporation of fair use protections into the DMCA’s notice-and-takedown regime, thanks to the dedicated folks at The Electronic Frontier Foundation and a dancing baby. In 2007, Stephanie Lenz posted on YouTube a 29-second video of her child dancing in her kitchen while Prince’s “Let’s Go Crazy” played in the background. Universal Records sent YouTube a takedown request, claiming infringement. EFF took up Lenz’s case, asserting fair use and, eventually, the courts agreed (opinion). Now, in the 9th Circuit, copyright holders must at least consider whether a fair use applies before sending a takedown request.

So even if you’re not in the 9th Circuit, take a few moments to look for permissionless uses of copyrighted works (they’re everywhere) and weigh those uses in light of the four factors: Is the work used in a different way, or for a different purpose than the original? What kind of work was the original and how much of it was used? Will the use hurt the market for the original? Then think about how different our culture would be without the ability to reuse works. Indeed, the fair use memes that appear throughout this post, the search used to find them, and their incorporation here all rely on fair use. From book quotes and campaign videos to political parody and clips showing the world your baby’s dance moves, fair use shapes and enables our interaction with copyrighted works, promoting innovation and free expression.

This week is Fair Use Week, an annual celebration of the important doctrines of fair use and fair dealing. It is designed to highlight and promote the opportunities presented by fair use and fair dealing, celebrate successful stories, and explain these doctrines.