Cybersecurity & Standards, Elections & Democracy

Election Officials Need Timely Information about Data Breaches and Network Intrusions

In the United States, a lack of a comprehensive notification strategy for network intrusions and data breaches in election systems undermines national interests and security. The Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) crucial role in coordinating the protection of election systems as a critical infrastructure should include a plan for broad notification about data breaches and network intrusions to both election system owners and state-level Election Directors responsible for certifying the election results. This is not currently the case. An example of why this is a problem occurred in Colorado, when DHS officials only notified the election system owner of an intrusion but failed to notify the state election director of the Russian hacking attempts. Notifying both the local election official as well as their respective chief election officer would overcome a confusing patchwork of state notification regulations, lead to more effective mitigation of the impact of intrusions and breaches, and foster communication between states and DHS.

Speaking to the public with a unified voice reinforces a much-needed level of confidence in the resiliency of our election systems.

Network intrusions and data breaches can have lingering impacts for affected individuals. Personally identifiable information (PII) is the most common type of data stolen in a data breach. However, voter registration databases also contain other valuable bits of information such as residential address and party affiliation. These data points can be used to further target individuals for identity theft, propaganda messaging, or bypassing security questions in order to gain unauthorized access to social media and bank accounts. The full impact of the data theft may not be realized for years or even decades since data from multiple data breaches can be combined and exploited.

Here’s a look at the current state of elections and data breach policy and steps that should be taken to improve it.

Current Confusion Around Elections & Data Breaches

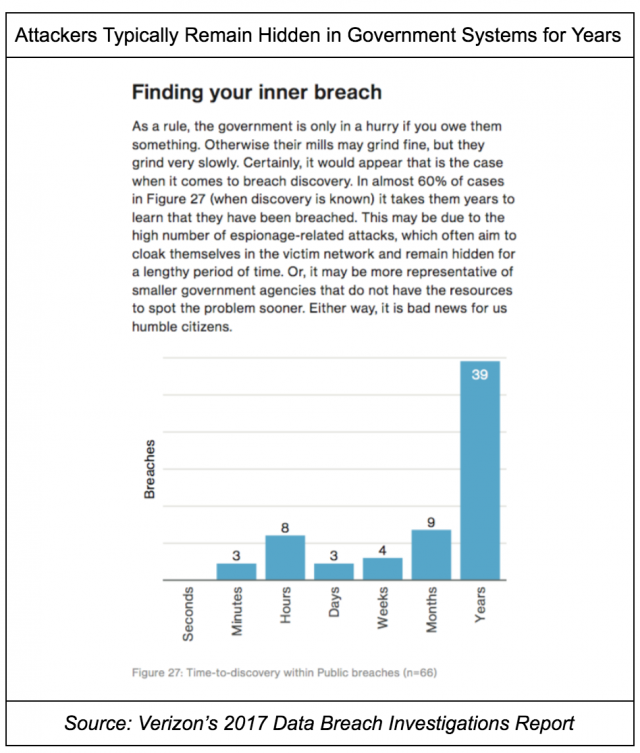

A lack of harmony among state laws, combined with duplicative and conflicting federal government guidance on notification, has created confusion and uncertainty about DHS’s reporting obligations. According to NCSL, “Forty-eight states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands have enacted legislation requiring private or governmental entities to notify individuals of security breaches of information involving personally identifiable information.” This confusing patchwork of state legislation is due to the lack of harmonizing data breach notification legislation from Congress. A strong case can be made that state election directors should be notified immediately by DHS about network intrusions and data breaches in order to work with election system owners on mitigation and recovery operations. Attackers typically have months or years to roam around government systems until their intrusion is discovered. Waiting an additional 30 to 60 days (or longer), as allowed by some state laws, for notification only worsens the predicament. Intrusion and breach notification for election systems is further complicated by the fact that “only half of the senior state election officials have received federal security clearances this year”.

Mitigating the Impact of Intrusions & Breaches

Timely notification and rapid response are also critical in limiting the impacts of an intrusion or data breach. Notification is crucial to stopping an active network attack, and mitigating the impacts of a data breach such as the manipulation of voter registration information or ballots. Notification of an attempted or successful data breach can come from a variety of sources including the individual attacker, the public, internal network intrusion detection tools, information sharing and analysis centers, industry communication networks, and DHS. Part of this information sharing includes security analysts reviewing network traffic and system activity to develop and share indicators of compromise (IOC) and network signatures – these the technical terms for the actionable intelligence that other system technicians need in order to block an attacker from spreading throughout a network, executing commands, and potentially stealing or destroying data.

Improving Communication Between DHS & Stakeholders

Communication provides the opportunity to build trust and galvanize the relationship between not only election officials and DHS, but also with election systems vendors and the public. As with notification and mitigation, effective communication requires a commitment to understanding that timing is of the essence, and partnerships are a key element of that timing. Though DHS offers a catalog of cybersecurity services for election infrastructure, for example, few local election officials were aware of these resources until very recently. Election systems vendors also play a role in this partnership. Absent investigation by independent security researchers, vendors are the only source of technical information about software and hardware vulnerabilities. Local election officials need to be able to depend on established, coordinated channels of communication with their state chief election officer, DHS, and vendors so that everyone involved in protection, detection, and mitigation can work from the same information set towards the same goals. Speaking to the public with a unified voice reinforces a much-needed level of confidence in the resiliency of our election systems.

In Practice

In the Summer of 2016, just months before the US presidential election, Arizona’s Secretary of State received a call from the FBI. It turns out that an employee that works with Arizona’s statewide voter registration database had been phished, clicking on a link that was used to steal their username and password to the voter registration system. The FBI was tipped-off about this when the credentials were found for sale on the Dark Web. Armed with this information, Arizona was able to immediately respond by shutting off all external access to the system and resetting the credentials of all users. This meant a week or more of downtime for a system that was essential for the upcoming election. However, the situation could have been much worse if the attackers had successfully sold those credentials or used them to modify or disrupt voter registration. This is an example of intrusion and breach notification working well.

Conclusion

DHS needs to further embrace its unique role in the protection of this newly-designated critical infrastructure sector by orchestrating the dissemination of actionable intelligence to those who directly manage election systems and to those accountable for certifying election results. This includes notification of network intrusions and data breaches of state and local election systems, and the systems operated by election vendors. Nearly every state has a legislated process for mitigating the impacts of data breaches on its affected systems and residents. While not specifically called out, the effects of network intrusions (sometimes just the digital equivalent of rattling a door knob or peeking into a window) are also mitigated by the efforts of system administrators to prevent data breaches. However, states cannot address a situation that they are in the dark about. Communication of timely and actionable information to local election officials as well their respective chief election officer is a crucial component in building resiliency and confidence in our election systems.