Government Surveillance, Privacy & Data

The U.S. Government is Demanding Social Media Information From 14.7 Million Visa Applicants – Congress Should Step In

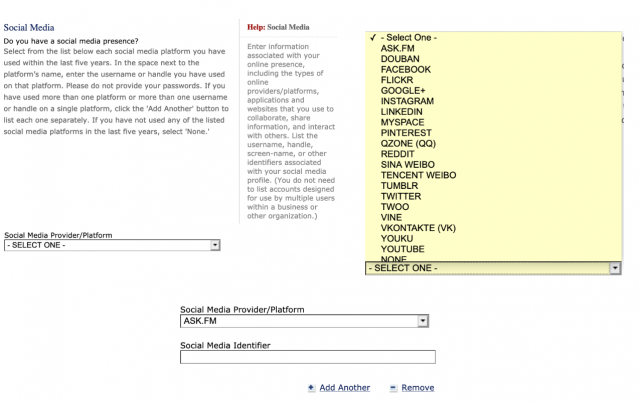

Despite opposition from CDT and our coalition partners in civil society, the U.S. government is demanding that most visa applicants—14.7 million of them—provide their social media identifiers as a condition of entry to the United States. The data collection was proposed March 2018, and is part of the Trump Administration’s heightened scrutiny, or “extreme vetting” of immigrants. The proposal was approved through a federal regulatory process in April. As of May 31, 2019 visa applications will now include the below additional field:

This question requires applicants to select all of the social media platforms they have used in the past five years and provide their associated social media identifier.

This collection will curb the exercise of rights, is too vague, and has not been proven to be necessary.

CDT repeatedly sounded the alarm that demanding social media information will chill visa applicants’ exercise of their rights to freedom of speech and association, as well as their right to anonymity. Applicants will feel pressure to self-censor, delete their social media accounts, and disengage from online spaces rather than risk denial of a visa, with negative consequences for their social, political, and business activities. For example, such individuals could feel pressure not to criticize a U.S. policy, or the policies of our allies. Applicants may also limit their social media engagements for fear that casual connections on social media may be perceived as a suspicious affiliation. For example, the State Department could perceive an applicant’s relationship with a Facebook friend or an Instagram follower as an intimate association, even though social media connections need not be based on any actual relationship. Visa applicants will no doubt take steps to protect themselves, limiting their engagement on these platforms and restricting the individuals they connect with.

In addition to the significant chilling effect this collection would have, the requirement to report all social media handles for these 20 platforms scopes too broadly: it is not reasonable to expect a visa applicant to remember all of the platforms they have used in the last five years. The average person has 7.6 active social media accounts, with the number rising to 8.7 for those aged 16-34. Visa applicants may temporarily create an account and try a new social media platform. Unlike a primary email account, a social media account is often not permanently adopted, and platforms may not stay in business very long. For example, Vine emerged in 2012 and shut down by 2016. An applicant could have easily created an account on the service and long forgotten about it—but the State Department is expecting her to report that account until 2021. Furthermore, “use” is not defined. Is an applicant “using” a platform if they log in to their account and do not post or engage with any content? Unclear.

Underlying these problems is the fact that social media communication is idiosyncratic and hard to interpret. Deciphering the meaning of statements is difficult without an intimate understanding of the context in which they are made. Parsing meaning from text is particularly arduous when communications employ slang, sarcasm, or non-textual information including emojis, GIFs, and “likes.” Visa applicants’ social media content will also often contain foreign languages, further increasing the complexity of analyzing this information. Interpretive errors are thus not only likely, but inevitable, and the relevance and value of social media is likely to be minimal. Given the scale of this collection the government could attempt to implement an automated vetting system. Such a system would be inherently technologically deficient and prone to discrimination, as explained in CDT’s white paper on automated social media content analysis, Mixed Messages.

The State Department has not demonstrated that social media data will provide it with the ability to better enforce immigration regulations, nor identify security threats. Again, the data is difficult to assess, and there is no evidence to suggest that State has developed a strategy for evaluating it. Rather, this screening will be comically easy for bad actors to circumvent. Knowing that the State Department will be combing through social media data, bad actors can simply fail to disclose their accounts, or disclose only newly-created, sanitized social media accounts to evade detection.

Finally, this solicitation will needlessly cause visa applicants to commit nominal errors in their applications, ultimately leaving them vulnerable to arbitrary denial of a visa or potential future denial or revocation of naturalization or of another immigration benefit. The State Department has yet to clarify the consequences of an oversight or mistake in filling out this field. However, failure to disclose might be viewed as a misrepresentation and could, according to a State Department official, result in “serious immigration consequences.”

Congress needs to act

The fight over this data collection is not over and Congress should act. Specifically, Congress should:

- Interrogate the assertion made by the State Department that the collection of this data is necessary to fully vet individuals, and provide needed oversight of State’s activity. For example, the State Department has solicited social media data for over two years from a subset of visa applications, and no known audit or assessment has been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of that smaller collection;

- Ask the State Department if it has audited this smaller program and demand it provide the policies and procedures that govern its social media screening to ensure they are rights respecting; and

- Demand that the State Department publish a Privacy Impact Assessment for this new data collection, which would require the Department to systematically assess the associated privacy risks.

Beyond these actions, Congress should also demand answers to the following:

- What are the consequences of a mistake that results in failure to report a social media identifier used in the past 5 years?

- Will social media data be reviewed for all or most visa applicants, and if not, what will prompt a review of a visa applicant’s social media data?

- What steps will be taken to ensure that visa adjudicators respect the right to free expression of visa applicants and don’t turn them down because they criticize the U.S. government, U.S. government policies, or U.S. leaders, such as the President?

- If the State Department makes a negative decision based on social media data content, will the applicant be informed and provided an opportunity to explain or rebut inferences drawn?

- Will adjudicators and investigators be instructed on what they are assessing when they review social media data?

The State Department has a responsibility to answer these and many other questions, and to craft standards and rules of conduct that safeguard against discrimination and other forms of abuse.

It won’t be long before another government emulates the United States and begins demanding Americans’ social media information as a condition of admission. As a country we have to ask ourselves: are we modeling respect for the human rights we value, like freedom of speech and association? With this move by the State Department, the answer is a resounding no.