Reflecting on 20 Years of the Patriot Act: U.S. Surveillance Authorities Must Still Change

The day before the Patriot Act passed in October 2001, Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT) founder Jerry Berman warned, “This bill has been called a compromise, but the only thing compromised is our civil liberties.” This week, CDT hosted a discussion looking back at the enactment of the Patriot Act and the expansion of government surveillance after 9/11, evaluating how the landscape for government surveillance authorities and civil liberties has evolved in the 20 years since, and exploring how we should go forward in the present day.

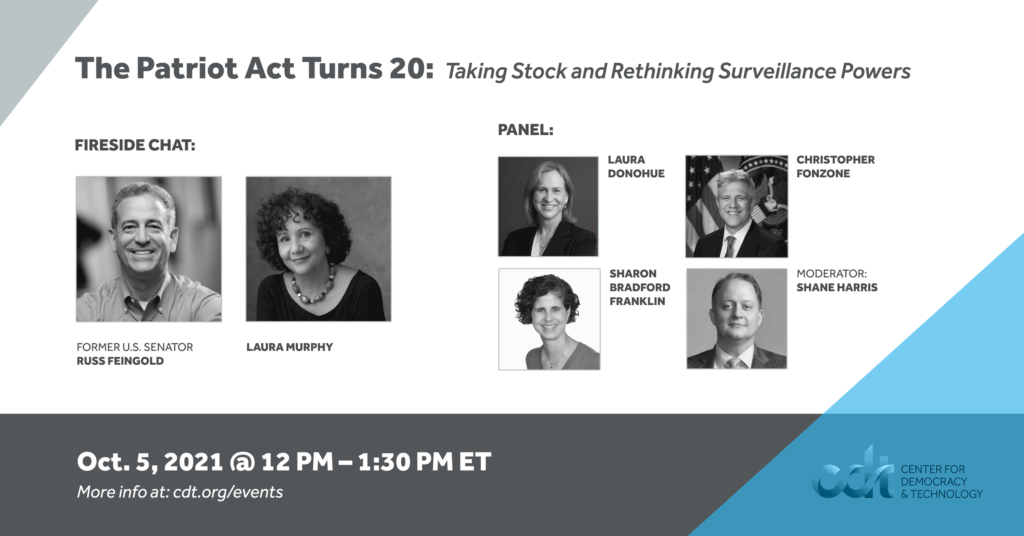

The event began with a fireside chat between former U.S. Senator Russ Feingold, the lone “no” vote in the Senate against the Patriot Act, and Laura Murphy, who managed the ACLU’s Legislative Office in Washington, D.C. at the time of the bill’s passage.

The two reflected on the speed with which the bill moved through Congress, despite containing “an old wishlist of the FBI… because they knew it was going to pass.” Feingold remarked that many other members of the Senate admitted that they never read or even gained a basic understanding of what was in the Patriot Act. But their review, said Murphy, revealed that “some of the authorities went far beyond anything we could have imagined.”

At the time, polling across the country revealed that people were — presciently — worried about the government snooping, including on what they were reading. In the years since, both Feingold and Murphy felt vindicated for pointing out the major civil liberties concerns with the legislation, and they both stressed the importance of having conversations in the present day about how civil liberties should be protected for everyone’s benefit.

Following the conversation between Feingold and Murphy, Washington Post reporter Shane Harris moderated a panel discussion between Laura Donohue, Director of Georgetown University’s Center on National Security; Chris Fonzone, General Counsel at the Office of the Director of National Intelligence; and Sharon Bradford Franklin, Co-Director of CDT’s Security & Surveillance Project.

Franklin highlighted a consistent thread in CDT’s advocacy since 2001: that we want the government to keep us safe, and we also need robust guardrails for government surveillance with firm roots in our legal system. But the period around 9/11 begot what Harris called radical changes, and sometimes secret reconsiderations, to longstanding surveillance laws. Said Franklin, “A problem with the Patriot Act was that it removed guardrails that had been in place, or failed to extend guardrails for some of the new authorities that were being created.”

In evaluating the decisions made in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, Fonzone said, “The first thing I’d flag that we got wrong is that we overshot, and as we’ve gotten further from 9/11, we’ve pulled some things back, and that’s something we’ve gotten right.”

The Patriot Act expanded the ability of government to obtain a broad range of business records without a warrant, and to issue National Security Letters or administrative subpoenas — and for both of these authorities, it removed the requirement that the government show that the information related to a foreign power or an agent of a foreign power. Section 702, a program that allows warrantless collection of the content of communications, had its origins in the top secret Stellar Wind program conducted under a claim of inherent presidential power and was then codified by Congress in the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Amendments Act, also remains problematic: among other issues, once the government has collected information, current rules allow it to search that data for information about specific Americans without a warrant or court review.

The panelists continually returned to the impact of the Snowden revelations on the debate over U.S. government surveillance. According to Donohue, at the time of the June 2013 leaks, only six Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) cases were in the public domain, and now there are about 100. She also pointed out that, once the government’s secret interpretation of Section 215 of the Patriot Act was revealed by Snowden and found to be illegal, all three branches responded: the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB) became higher-profile, President Obama put together a review board and issued Presidential Policy Directive 228, and the FISA court — which had never had a public filing — then had 160 within a year.

In that same year, Members of Congress introduced a broad range of proposals to reform government surveillance, ultimately resulting in enactment of the USA FREEDOM Act of 2015. The bill, which Murphy called the first substantive amendment to the Patriot Act, purported to end bulk collection of Americans’ communications information under Section 215, among other reforms.

Donohue said that USA FREEDOM “shifted the landscape, to allow the court to hear from parties adversarial to government surveillance.” The law created the role of amici, or friends of the court, but Franklin said that there is still a need to expand the cases in which amici appear, give amici full access to information in the matters in which they appear, and let amici petition for an appeal to the FISA Court of Review or Supreme Court.

Fonzone agreed that the role of amici is important: “The fact that the government is willing to subject its arguments to the court, have an amicus come in and make counterargument, appeal it, and then when it loses take the court’s order, that I think is the system working that we’ve set up.” The panelists further discussed what constitutes counsel that is functionally adversarial to the government, and the government’s fiduciary duty to the kinds of arguments it makes behind closed doors to a court.

Other areas of concern mentioned by the panelists include government abuse of state secrets privilege to get entire suits dismissed; the extent to which judicial opinions remain classified; and oversight of government surveillance beyond the FISC. They also included loopholes in the Electronic Communications Privacy Act that allow the government to bypass requirements for warrants or other judicial orders by purchasing information from data brokers; how to fit new technologies into old statutory language; and the separation of powers issues posed by the specialized nature of the FISC.

Going forward, the panelists concurred with Fonzone that, in this post-9/11 national security era, we need to be able to constantly consider the types of authorities we have in the U.S., and whether they are the right ones. Fonzone specified that this process should be as transparent as possible, and Donohue highlighted the continued importance of fidelity to law, judicial discretion, and established processes.

Fonzone and Franklin drove home that other jurisdictions are also playing a role in prompting a debate over surveillance authorities — particularly following the decision by the Court of Justice of the European Union that struck down the Privacy Shield, citing insufficient safeguards under U.S. surveillance law for protections of personal data.

Franklin added, “That’s another opportunity for our government to take a long, hard look at our surveillance laws and adopt reforms. There’s a lot the government can do without Congress. We need to move forward with a comprehensive review of our surveillance laws in a meaningful way.” And the 2018 decision in Supreme Court case Carpenter — which held that the government needs a warrant before collecting sensitive location information — has given her hope: “If you think through the analysis of Carpenter and what it recognized about sensitive information that reflects the privacies of life, you would come to the conclusion that [the warrant requirement] covers a lot more information in a lot more contexts.”

The full event is available to view on CDT’s YouTube Channel.