Government Surveillance, Privacy & Data

Limiting Face Recognition Surveillance: Progress and Paths Forward

Face recognition is a powerful and invasive surveillance technology that continues to grow in use across the United States. Half of all federal agencies with law enforcement officers use face recognition. Clearview AI, just one of many vendors, is used by more than three thousand police departments, about one in every six across the country.

If we want to preserve privacy rights, it’s critical we put guardrails on this intrusive yet increasingly common surveillance tool.

Significant Progress in States Over the Past Five Years

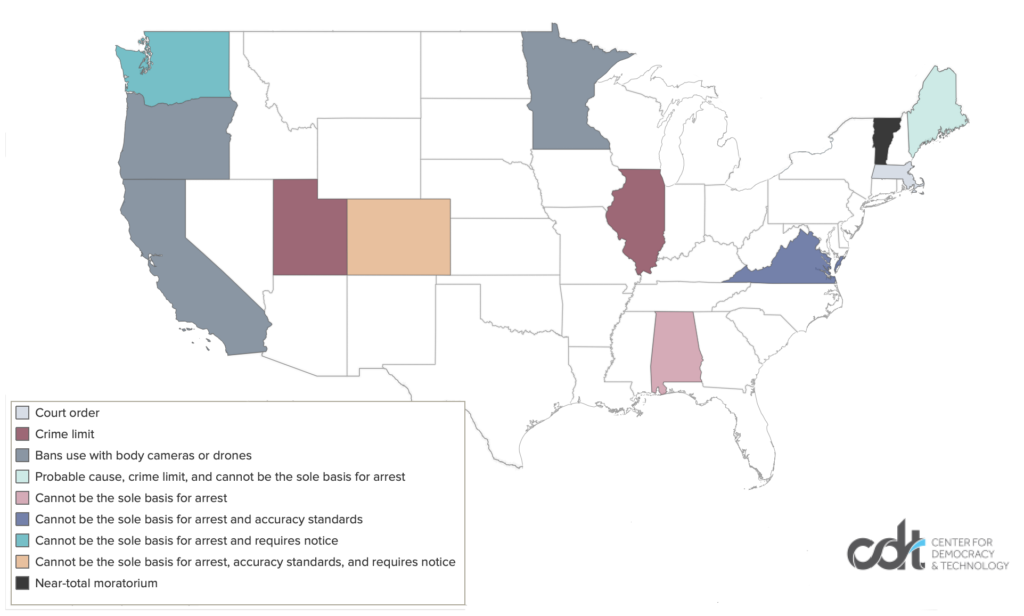

Fortunately, states have made progress in enacting strong limits over the past few years. Five years ago, only one state, Oregon, had any laws limiting face recognition: a prohibition on using it in combination with police body cameras. By 2019, numerous other states had followed suit, enacting similar prohibitions on use with body cameras. Since then, there has been a breakout. As of this year, more than a dozen states have laws limiting face recognition surveillance in some capacity, including a variety of policies such as restricting what crimes it can be used to investigate and requiring the government to notify defendants when the technology was used. One state — Vermont — has even enacted a near-total moratorium on face recognition, prohibiting its use in all situations except for investigations related to sexual exploitation of minors.

Laws passed in the last few years reflect growing momentum, but also leave much to be done to properly protect all Americans.

What Should Congress Do?

Even if states continue to enact limits on face recognition, Congress needs to step in and act on this issue. That is the only way to control how face recognition is used by federal law enforcement agencies like the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). And state laws currently impose a hodgepodge of different policies, with none providing the full set of safeguards necessary to protect individuals’ rights.

Ideally, we would press pause on face recognition surveillance, examine the technology’s risks and shortfalls, and have a public debate about what uses should be permitted and what rules should be imposed to address the risks from law enforcement and immigration enforcement use of face recognition. That’s why CDT has praised the Facial Recognition and Biometric Technology Moratorium Act, which would halt government use of face recognition until Congress can enact a comprehensive set of rules to mitigate the threats to human rights.

But with face recognition already a common surveillance tool across the country and in the absence of a moratorium, Congress should move quickly to put in place the most effective limits to protect civil rights and civil liberties and prevent overbroad surveillance. The key limits to face recognition (we do not address here one-to-one matching to verify identities, such as where the Transportation Security Administration matches faces to photo ID to expedite security checks) include the following six measures:

1. Warrant requirement

Court approved warrants based on probable cause are a fundamental safeguard for surveillance activities, such as searches, wiretaps, and monitoring emails; this measure should be extended to face recognition as well.

A warrant rule — specifically, requiring law enforcement to show a court there is probable cause that any individual whose face it wishes to identify using face recognition has committed a crime — is a critical protection against dragnet surveillance and abuse. Without a warrant rule, police might use face recognition to stockpile identities of individuals participating in protests, going to their house of worship, or seeking aid at a medical clinic, by claiming such surveillance has a nexus to a crime or was useful for law enforcement intelligence gathering. There are already documented cases of this: in 2020, multiple Florida police departments used face recognition to identify Black Lives Matter protesters absent suspicion of wrongdoing.

While warrants would provide significant protection for civil rights and civil liberties, they would not be any more burdensome to legitimate law enforcement needs. Currently law enforcement predominantly employs face recognition for investigative use: police have a photo of an unidentified suspect during commission of a crime, and use face recognition to find a possible match. In such a scenario, demonstrating probable cause would not be onerous. Thus, a warrant rule would simultaneously be a strong barrier against abuse without preventing reasonable uses.

No states currently require a warrant to use face recognition. Massachusetts requires a court order for scans, but rather than probable cause, the government merely needs to show that identifying the individual is relevant to an investigation. While court approval limits risk of abuse, this relevance standard is far too low, leaving the door open to broad face recognition scans of everyone with any nexus to an investigation (such as all individuals at a protest where an act of vandalism occurred). Maine requires probable cause for face recognition scans, but does not require demonstrating this in court. For such a powerful surveillance tool this type of self-regulation is dangerous, risking lax compliance and abuse. An effective law should establish a warrant requirement that includes both a strong probable cause standard and court approval.

2. Serious crime limit

Another crucial policy for face recognition surveillance is limiting its use to investigation of serious offenses. This type of policy has longstanding precedent: for over 50 years, wiretaps have been subject to a serious crime limit.

A serious crime limit is especially important for face recognition given how much the technology could facilitate abuse of discretionary powers and selective targeting. We’ve already seen this in practice: in 2015, in response to mass protests against police brutality, Baltimore police used face recognition to scan crowds of demonstrators and arrest individuals with unrelated outstanding warrants. Absent a serious crime limit, the government could use face recognition to selectively enforce bench warrants for minor offenses (like unpaid tickets or missing a call from a parole officer) against marginalized communities and political dissenters. China’s surveillance state already paints a grim picture of how harmful weaponizing face recognition for low-level offenses can be: Individuals are shamed for “uncivilized behavior” and targeted for jaywalking, with effortless enforcement of minor offenses being used for unprecedented social control.

A serious crime limit for face recognition is also important to ensure careful use of a technology that is not just powerful, but also highly complex and often mistaken. Many face recognition algorithms are error-prone — with significantly higher error rates for women and people of color — and even “top ranked” algorithms can be unreliable if paired with low-quality images or lax system settings. It’s perilous to allow face recognition to be used for minor offenses that often receive little scrutiny, and are frequently resolved through plea bargains before defendants can carefully examine if the technology was used in an unreliable way.

Two states have instituted a crime limit for face recognition: Maine limits use of face recognition to “serious crimes” (defined in the bill), and Utah only permits face recognition for investigating “a felony, a violent crime, or a threat to human life.” Congress should follow suit — albeit with more stringent restrictions than these states have enacted — and limit use of face recognition to investigating serious offenses such as homicides.

3. Notice to Defendants

Despite how frequently face recognition is employed by law enforcement, its use is often hidden from defendants and judges. Law enforcement will often obscure use of face recognition in warrants and affidavits with vague language such as “investigative means,” and rarely disclose its use to defendants.

Lack of disclosure can create significant due process issues, especially for face recognition. A defendant can’t challenge the reliability of a face match if they don’t know whether or not face recognition was used in the investigation that led to charges against them. Whether any given face recognition match provided an accurate lead or should cast doubt on a prosecution depends on a variety of factors: algorithms vary in quality, with some algorithms being 100 times more likely to misidentify Asian and Black individuals than white men. As stated before, low quality images are far less likely to return accurate results and system settings can make the odds of an erroneous match far more likely. For example, many law enforcement entities set face recognition systems to always return a set of potential matches, no matter how unreliable the results are. Most troublingly, police sometimes use junk-science applications of face recognition, such as using CGI imaging to draw part of a face or a celebrity look-alike.

Just as we expect the government to disclose what samples it uses for a DNA test or what methods it applies to fingerprint comparisons, we should expect it to reveal how it uses face recognition matches. Disclosure is critical for defendants’ rights, as well as a safeguard to deter corner-cutting and sloppy uses of the technology during investigations.Currently two states — Colorado and Washington — require the government to disclose the use of face recognition to defendants before a trial. Congress should pass legislation to ensure defendants across the country have timely access to all relevant information about how face recognition was used in investigations.

4. Cannot Be Sole Basis for Arrest

Another key safeguard to limit the harm of error in face recognition systems is restricting the extent to which matches can be relied upon for police action. There are already three documented cases where individuals were arrested and held in jail solely because they were wrongfully identified by a face recognition system. Because of how often the use of face recognition is hidden from defendants, courts, and the public, the actual number of improper arrests based on face recognition is likely much higher.Not letting face recognition be the sole basis for arrest — or itself serve as probable cause for other police actions, such as a search — is a commonsense measure. Many law enforcement entities, including the FBI, have already voluntarily enacted policies requiring that face recognition matches not be the sole basis for arrests. And now numerous states have built this requirement into law: Alabama, Colorado, Maine, Virginia, and Washington all prohibit a face recognition match from serving as probable cause for a search or arrest. This basic measure should be required nationwide.

5. Prohibition on Untargeted Scans

Untargeted face recognition — in which, rather than scanning and identifying a single target, a system identifies all individuals in a video feed — is the most frightening use of this technology. It could be lead to draconian surveillance, such as effortlessly stockpiling the identities of everyone at a protest, cataloging each person that attends service at a mosque, or scanning for undocumented individuals outside hospitals and schools. China already uses untargeted face recognition for mass-scale social control and the targeting of minority populations, specifically Uyghurs.

These systems are also dangerously prone to error. In the United Kingdom , false positives range from 81 to 96 percent (there are currently no known public deployments of untargeted face recognition in the United States). That means these systems could result in police officers improperly stopping and detaining a huge number of individuals that are wrongfully identified as threats.

With such significant potential for abuse and no clear remedy, untargeted face recognition should be off the table. Currently no states have a ban on untargeted scanning; Colorado and Washington require a warrant for “real-time” scanning of video feeds, and Virginia law contains a vague limit against using face recognition to track individuals. Whether a warrant requirement for face recognition scans prevents untargeted scanning depends on how such a legal standard is written. For example, Maine law — which requires “probable cause to believe that an unidentified individual in an image has committed the serious crime” — should prevent untargeted scans. However Massachusetts law, which requires court approval but not a full warrant (specifically requiring a court order that “information sought [from face recognition] would be relevant and material to an ongoing criminal investigation”) might be read to permit untargeted scans. Even if a well-written warrant rule exists, lawmakers should include a separate prohibition on untargeted scans for added clarity.

6. Testing and Accuracy Standards

Due to the serious accuracy problems with some face recognition algorithms, testing and accuracy standards are crucial to limiting misidentifications, and ensuring the dangers posed by errors are not predominantly borne by people of color, and other demographics for whom face recognition is less accurate. In order to be effective, testing should be conducted by an entity with independence and expertise, such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Standards should require a high bar for overall accuracy, and prohibit use of algorithms that display any variance in accuracy based on demographics, such as gender, race, ethnicity, or age.

Testing should be based on images reflecting the same field conditions as images that law enforcement will subject to face recognition scans. Photos with bad lighting, low resolution, poor angles, or obstructions are much less likely to return accurate results. But these conditions are often present on images law enforcement are scanning, such as CCTV footage from a crime scene. Testing should examine how well face recognition systems work in these real-world settings.

Currently, Colorado requires testing of systems for overall accuracy and demographic bias, although if demographic bias is discovered the law merely requires the vendor “mitigate” this problem, rather than fully eliminate it. Virginia requires any face recognition system be tested by NIST prior to use, and display “minimal performance variations” based on demographics (emphasis added). This requirement will help prevent some algorithmic bias, although it would be far more effective if the law prohibited any statistically significant variation.

Testing is an area where Congressional efforts to establish national standards could aid civil rights and civil liberties, as well as create clear and consistent benchmarks to ensure systems are properly vetted.

Conclusion

We are at a tipping point: as surveillance cameras become increasingly ubiquitous and more law enforcement entities deploy face recognition, unregulated use of the technology could soon become the norm, while anonymity in public becomes a relic of the past. Every movement, activity, and interaction could be tracked and logged.

Or, we could build in sensible limits and ensure that, as the government’s capabilities to effortlessly monitor us grow, so do safeguards that limit those surveillance capabilities and protect our privacy. We should seize the opportunity to keep face recognition surveillance in check, and enact stringent rules limiting where and how the government may use it.