Financial Dashboards: Enhancing User Control Outside a Traditional “Privacy Dashboard”

Privacy dashboards are often put forward as a potential solution to the vexing problem of offering individuals control over their personal information. Ideally, a dashboard could provide both insight into how users’ information is collected and processed and provide users with meaningful options that can protect their privacy. Industry actors have been iterating on the concept for years, but regulators of all stripes are well-positioned to provide useful guidance and best practices to improve dashboards as a form of user control.

Already, privacy regulators have been solicitous of the dashboard concept. The Federal Trade Commission, for example, called for the creation of a “one-stop” shop to review what types of data is accessed by mobile apps. The agency advocated for a similar approach in its Internet of Things report, calling for companies to implement “command centers” for connected homes and other smart devices. Data protection authorities in Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, as well as the EU’s Article 29 Working Party, have also suggested that dashboards can promote user control by improving the granularity of privacy settings presented to users.

The result has been a wide proliferation of dashboards. But as these tools have multiplied, some of their limitations have also become apparent. For one, the sheer variety of different control mechanisms offered by mobile platforms, internet service providers, data brokers and other data-driven companies, and now IoT devices can make effective and meaningful privacy management overwhelming. Second, there is no standardized set of controls, and the amount of user control being offered by these tools varies considerably. Dashboards frequently focus on providing information and control over how data is used rather than provide any options over how it might be initially collected. Finally, there is little accountability to users about whether their privacy settings are actually respected by different data processors and controllers.

The Search for Dashboard Best Practices

While there has been no consensus among companies or regulators on what makes up a good dashboard, ideal components might include a usable and functional interface, built on an open-standard and backed by clear regulatory guidance. However, several themes do emerge from statements on the subject by European and American regulators; surveying existing guidance, a recent report on user controls from the Institute for Information Law (IViR) at the University of Amsterdam identifies the following general requirements of a well-functioning privacy dashboard:

- Accessibility: Dashboards must be easily accessible, and information about the tool should be provided by third parties and partner websites also receiving data.

- Default-Settings: Default settings should ideally be set in the user’s interest but must, at minimum, be adaptable across different jurisdictions, and any control mechanism should have a “restore to default” feature.

- Granularity: Controls should ensure users have ongoing access to permission different types of data processing, and permissions should provide detail into which third parties have received data.

- Usability: Granularity must also be balanced against usability. A dashboard should be straightforward and its user experience well-designed. Most importantly, revoking consent should be as easy as providing it.

- Information and Transparency: In addition to a simple “on/off” button, information must be presented in such a way to properly inform users and explain the consequences of a given user control.

- Persistency: Settings chosen by users via a dashboard must be enforced upon third parties within a relevant ecosystem.

Some of these recommendations are in tension with each other. Balancing usability against, for example, control granularity and meaningful transparency could require compromises between user and regulator expectations or demands. Information overload is a very real threat to meaningful privacy control, leading to concurrent calls for “layered” notices, iconography, and other visual shortcuts that would facilitate user understanding. At the same time, technical challenges also exist outside these requirements. For example, an ideal dashboard would be appropriately centralized in a location users would frequently access and controls would scale across services and platforms. However, because data is often collected and shared in different locations and contexts and in different formats, “interoperability” of user privacy settings has been limited thus far in practice outside of closed ecosystems.

User Control and Fintech Intermediaries

While regulators and privacy advocates have focused almost exclusively on the notion of a privacy-specific dashboard, the dashboard concept can also promote user control of their information outside of the exclusive context of data protection. Speaking at the Technology Policy Institute’s Aspen Forum last year, former FTC Chairwoman Edith Ramirez spoke about the need for “privacy intermediaries” to convey information about data practices and manage user preferences. This sort of dynamic is beginning to emerge not in the world of data privacy but in consumer-facing financial services. For example, financial aggregators like Mint already offer users dashboards that provide insight and transparency into financial accounts; these tools could also be used to manage account access (and use) on a user’s own terms.

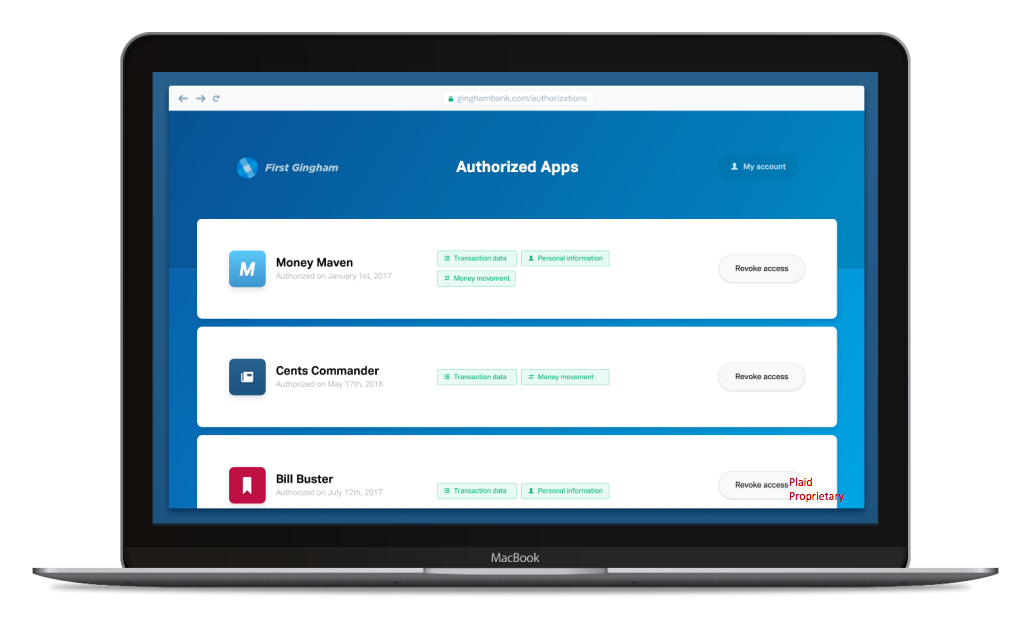

Improving individual access to and control over financial data is at the heart of a recent inquiry launched by the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. While everyone generally agrees that individuals should be able to access and port, or move, their financial data, stakeholders have different views on implementation and ease of use. One suggestion by Plaid, a fintech intermediary that provides permission-based financial account access, was to improve the functionality of online account portals offered by financial institutions. Specifically, banks could display which services and applications have access to account data in a centralized location. This could also promote granular controls. For example, combined with the use of authorization protocols, users could pick and choose what permissions to grant (for example, permissioning access to financial transactions but not bank balances) and easily revoke access at any time. This functionality could also be augmented by improving information flows during user onboarding when accounts are linked together, offering displays about what types of data permissioned parties are accessing, for what purpose, and for what duration in the dashboard itself.

Potential dashboard mockup proposed by Plaid in comments to the CFPB. One could envision a more elaborate, multi-layered portal that includes easy “on/off” buttons, as well as dropdowns and more information about what data are flowing where.

While these types of tools could have a meaningful impact on how users control their data, there are policy and technical challenges to be sure. Though banks are traditionally highly regulated, the baseline protections applicable to fintech providers and other apps and services involved in this ecosystem is less clear. More rigorous and clear privacy protections could help to ensure basic privacy protections are in place across the board.

However, different financial players also must learn to play nice. We have already seen some movement to limit sharing of actual financial account credentials; earlier this year JPMorgan Chase and Intuit announced a read-only API solution to tokenize account authentication using OAuth, improving the security of services like Mint. Bank-specific APIs for accessing account data are a start, but efforts such as the UK’s Open Banking Standard have promoted standardized open APIs — with a dedicated eye to protecting user privacy and security. An API-approach will require strong authentication protocols like OAuth, which might also include a permissions system to facilitate transparency and control over user’s data.

If industry collaboration cannot catalyze better experiences around financial data sharing, regulatory action in both the United States and European Union may also assist in providing firmer guidance and industry best practices to emerge in the near-term. The CFPB’s inquiry focuses on access rights to both accounts and account-related data and how these rights impact individual choice and control. Though the scope of the Bureau’s authority to mandate access standards under the Dodd-Frank Act is unclear, its RFI suggests it will pursue policies to encourage and facilitate concrete actions by banks, data intermediaries, and consumer and privacy advocates. On the other side of the Atlantic, the EU’s revised Payment Services Directive (PSD2) may also promote innovation around accessing and learning about financial information, facilitating both Mint-like “Account Information Service Providers” and promoting the use of account access via API.

A User Control Template

Privacy dashboards are frequently cited as a solution to the lack of control users have over personal data, but if the goal is to improve user control over their information and digital footprint, lessons can be learned and user control advances can be found in other fields. In the case of financial dashboards, they hold the promise of being easily usable, built on open-standards, and scalable across the financial ecosystem. Without overselling the promise of these tools, consumer demand for control over financial data seem to incentivize portals that meet a number of the potential dashboard “best practices” identified by IViR.

While the themes identified by IViR do not precisely map onto financial services, at minimum, dashboard controls could be made easily accessible and persistent via a user’s favored online banking portal. Plaid’s mock-ups provide a number of different avenues for providing both required and additional information and transparency, and usability studies by industry and financial regulators could go a long way to addressing how best to balance granularity and user experience. Finally, though default-settings traditionally have a strong influence on how users ultimately decide to configure privacy and other data sharing settings, open banking efforts may be a powerful constraint against financial institutions’ individual efforts to engage in cross-selling, and a properly deployed dashboard might even limit how financial institutions present personalized offers and marketing partnerships.

More importantly, lessons learned around data access in fintech and financial services should be brought to bear on developments in the privacy world. Regulators, for example, should highlight developments in dashboards broadly and could facilitate a repository of best practices and examples of tools that meet those standards. Bridging the innovation that already seems to be occurring in the financial sector with the desires of privacy regulators could prove a productive path forward for advancing meaningful user control technologies.