Correcting the Record: The ECTR “Fix”

Last week, Senators John McCain and John Cornyn proposed an amendment to an appropriations bill that would have permitted the FBI to obtain sensitive information, such as email records and browsing history, without a court order. While the amendment failed to meet the required sixty-vote threshold for moving forward, another vote is expected in the coming days on this proposed massive expansion of the FBI’s authority. Before it does, it is important to dispel several misconceptions that arose during the debate about the FBI’s access to the records at issue, “electronic communication transactional records” (ECTRs). With additional, accurate information on the proposed ECTR “fix”, hopefully more Senators will oppose this unnecessary and potentially dangerous amendment.

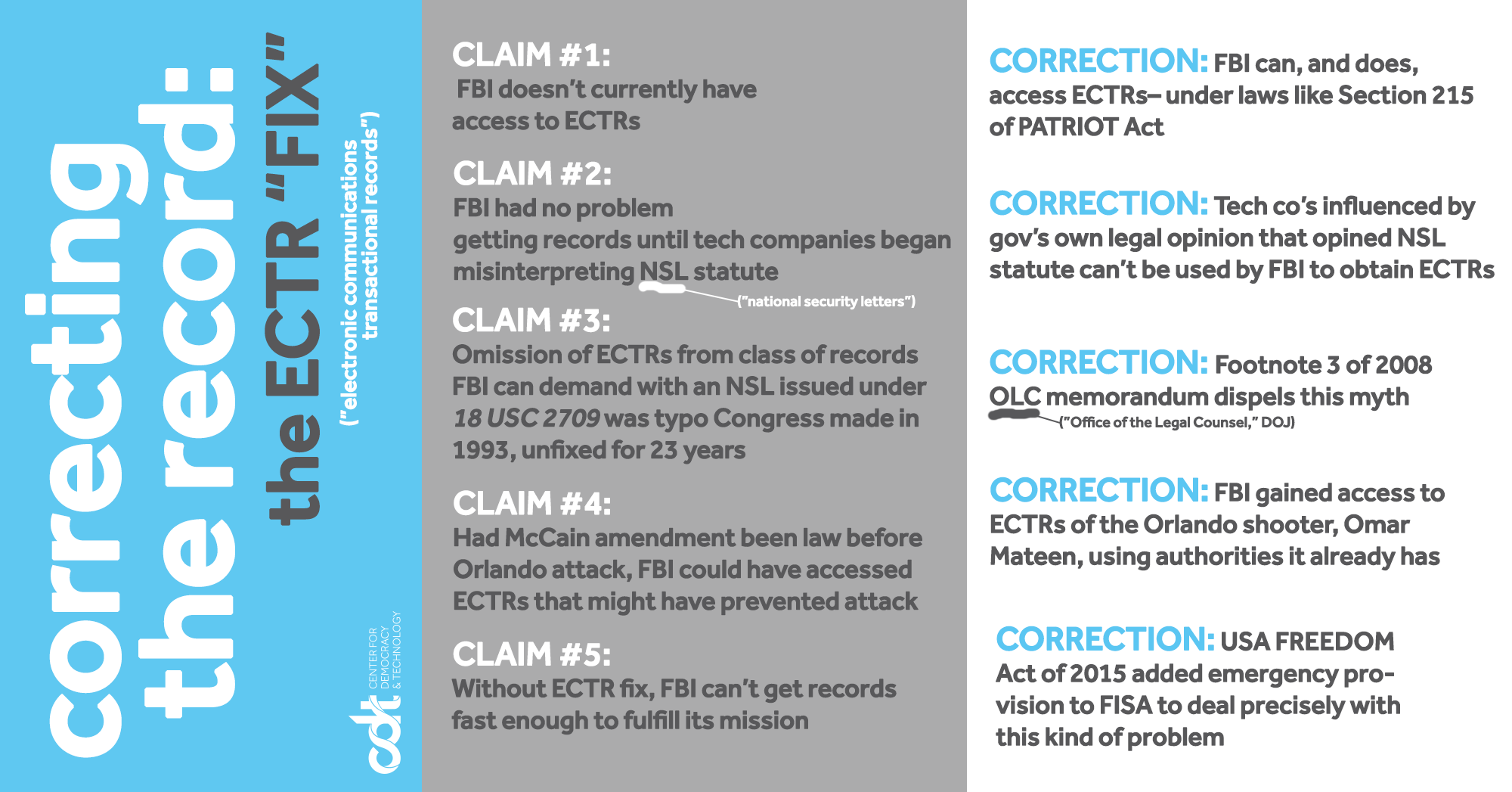

CLAIM #1: The FBI does not currently have access to ECTRs. “Currently, the FBI can obtain these non-content transactional telephone records and financial records but not internet records due to conflicting legal interpretations, which is hamstringing the FBI’s ability to obtain important information in national security investigations.” Sen. McCain press release.

CORRECTION: The FBI can, and does, access exactly the kind of information covered by the McCain amendment. Under Section 215 of the PATRIOT Act, the FBI has the authority to compel companies to produce any “tangible thing” relevant to a clandestine intelligence or terrorism investigation, including ECTRs. In fact, the types of investigations in which ECTRs can be obtained with a court order issued by the FISA Court under Section 215 are identical to the types of investigations in which the McCain amendment would authorize the FBI to obtain ECTRs with a national security letter (NSL). The standards are slightly different: under the McCain amendment, the FBI would certify that the information sought is relevant to an investigation. Under Section 215, the government has to provide a statement of facts showing that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the ECTRs are relevant to an investigation. The biggest difference is that under Section 215, the FBI has to convince a court that the ECTRs it seeks are relevant, whereas under the McCain amendment, the FBI need only convince itself.

CLAIM #2: The FBI had no problem getting these records until tech companies began misinterpreting the NSL statute on their own. Disclosure of ECTRs upon receipt of an NSL “…is clearly something that continued from 1993 until 2010, 6 years ago, when all of a sudden a tech company looked at it and said: Boy, it is in this subpart, but it doesn’t state it in that subpart so we are not going to provide it for you anymore. … All of a sudden, one company’s general counsel said: We don’t see it in this subpart; therefore, we are not bound to provide that for you.” Sen. Burr at S4436.

CORRECTION: It was actually the government’s own legal opinion that interpreted the NSL statute to bar the FBI from getting the ECTRs they now seek via NSLs. Tech companies stopped complying with requests in response to that 2008 opinion of the Office of the Legal Counsel (OLC) at the Department of Justice. The FBI asked the OLC whether the NSL statute authorized the FBI to issue NSLs for electronic communication transactional records and the OLC answered with a definitive “No.” The FBI, however, disregarded the OLC’s opinion and continued demanding records from tech companies. Only after that OLC opinion was published did the tech companies stop complying with such requests.

CLAIM #3: The omission of ECTRs from the class of records the FBI can demand with an NSL issued under 18 USC 2709 was a typo Congress made in 1993 that has gone unfixed for 23 years. “There is essentially a typo in the law that was passed a number of years ago that requires us to get records, ordinary transaction records that we can get in most contexts with a non-court order, because it doesn’t involve content of any kind, to go to the FISA court to get a court order to get these records. Nobody intended that.” FBI Dir. James Comey at S4388.

CORRECTION: The 2008 OLC memorandum dispels this myth. The OLC points out in footnote 3 that Congress used the term “electronic communication transactional records” to permit the FBI to issue an NSL to both ordinary telephone service providers and electronic communication service providers, but deliberately limited the class of records that could be sought from those providers to subscriber information and toll billing information. Far from being a “typo,” the 1993 amendment to 18 USC 2709 was a deliberate drafting choice to limit the scope of NSL authority. Moreover, ECTRs are not available in criminal investigations without a court order. An order, based on a showing of specific and articulable facts that the information sought is relevant and material to a criminal investigation, is required under 18 USC 2703(d).

CLAIM #4: Had the McCain amendment been law before the Orlando attack, the FBI could have accessed ECTRs that might have prevented the attack. “I wonder if the FBI had access to a national security letter that would allow them to gain information about the IP addresses [Omar Mateen] had been visiting from his Internet service provider, along with email addresses…” Sen. Cornyn at S4393. “Unlike some of the [gun control] provisions we voted on last night that would do nothing to stop people like the Orlando shooter, this [amendment] could actually stop them.” Sen. Cornyn at S4394.

CORRECTION: The FBI gained access to the electronic communications transactional records of the Orlando shooter, Omar Mateen, using authorities it already has. As FBI Director Comey said in the press briefing that followed the tragedy in Orlando, the FBI looked at Mateen’s transactional records from his electronic communications over the course of a ten-month preliminary investigation that was triggered by remarks he made to co-workers. In fact, Department of Justice investigative guidelines make it clear that the FBI currently has full access to ECTRs in preliminary investigations. Nothing in the McCain amendment would give the FBI access to information it cannot already obtain – and did, in fact, obtain – when it investigated the Orlando shooter.

CLAIM #5: Without the ECTR fix, the FBI can’t get communications transactional records fast enough to fulfill its mission. “[Requiring a court order for FBI access to ECTRs] means the FBI goes from a 1- day process of getting this vital information to over a month. To go to the FISA Court and get approval to seek the information—over a month. If it had to do with a terrorist attack, boy, I hope the American people are comfortable with saying: As long as the FBI figures this out a month in advance, then we are OK.” Sen. Burr at S4436.

CORRECTION: The USA FREEDOM Act of 2015 added an emergency provision to FISA to deal precisely with this kind of problem. Under the USA FREEDOM Act, the FBI can require companies to produce records, including ECTRs, immediately and without a court order. The FBI then has to seek court authorization after the fact, but has an entire week from the date of the emergency request to file an application with the court. The emergency exception thus adequately balances the needs of security and liberty by allowing the FBI to respond to emergency situations but still keeps courts involved through post-hoc review. All the so-called “ECTR fix” does, then, is completely erase courts from the process without actually making people any safer.

For further information, contact Gabe Rottman ([email protected]), Deputy Director, Freedom, Security and Technology Project, or Jadzia Butler ([email protected]), Privacy, Surveillance & Security Fellow.