Elections & Democracy, Free Expression

CDT Report: An Agenda for U.S. Election Cybersecurity

CDT, in collaboration with Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS), has released a report outlining an agenda for important U.S. election cybersecurity improvements for 2021 and beyond. The introduction of the report is pasted below, and you can read the whole report here.

***

Introduction: U.S. democracy in the digital age

Although no election is flawless, a functioning democratic government rests on the people’s trust in electoral systems to produce fair and accurate results. Yet, during political campaigns, and before, during and after the elections themselves, malicious actors can influence information flows; public opinion is often manufactured and manipulated; and digital and analogue election infrastructure continue to have weaknesses. Policymakers can support the work of election officials to ensure that the elections are fair, secure, and efficient, that voters have the ability to cast their vote without obstacle and, most importantly, that every vote is counted as intended.

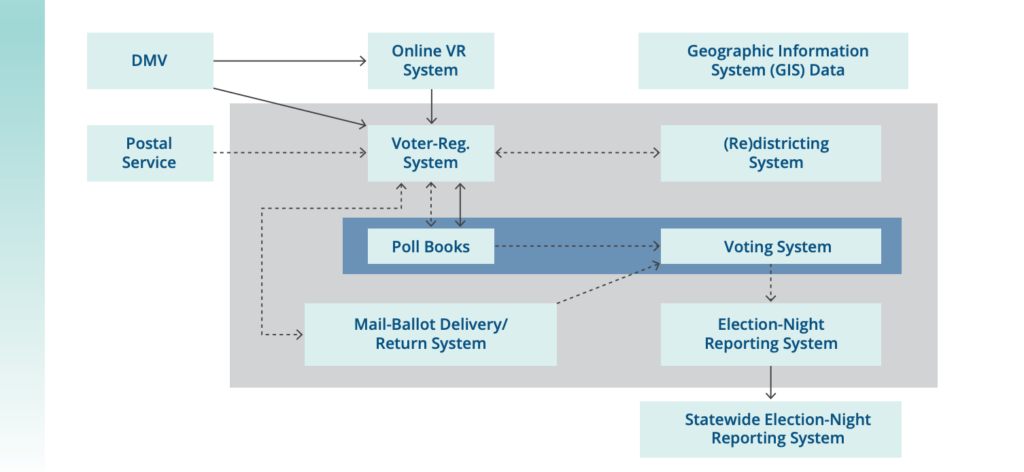

This year, the COVID-19 pandemic posed an extra challenge for election officials. But even without a pandemic, election administration is more complicated than it might seem at first glance. The following graphic, reproduced from election administration expert Charles Stewart III, depicts the components of election infrastructure and the paths by which information flows between them:

Reproduced from Stewart III, Charles. “The 2016 U.S. Election: Fears and Facts About Electoral Integrity.” Journal of Democracy 28:2 (2017), p. 56, Figure 2. © 2017 National Endowment for Democracy. Reprinted with permission of Johns Hopkins University Press.

Source: This schematic of voting information-system architecture is based on the work of Merle King. For King’s full schematic, see https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/itl/vote/tgdc-feb-2016-day1-merle-king.pdf#page=14.

It is critical to secure these connections and transmissions, especially those across the open internet, which are represented by solid lines in the figure. A cyber attack, ranging from data capture to manipulation, is possible any time information is transmitted over the internet. It is also critical to physically secure even the “air-gapped” components that are not connected to the internet. There are known security flaws with many components and machines still in use that could enable a hacker with physical access to change the software on a machine.

One challenge to secure elections is that responsibility for components of election infrastructure are spread across a large number of jurisdictions and authorities. The federal government sets some minimum standards for election machinery and operations and provides some guidance and assistance. States maintain voter registration databases and statewide results reporting systems. But counties and localities are responsible for running the elections themselves: checking people in, administering in person voting infrastructure, and tallying votes. This creates the possibility for diffusion of responsibility, making security dependent on good communication across federal, state, and local levels. Fortunately, there have been significant improvements in coordination in recent years.

Improvements to security are not only about ensuring that components cannot be tampered with, but also about improving trust. Even with no evidence of major problems in the 2020 general election, and with a coalition of election officials releasing a statement saying that the election “was the most secure in American history,” the weeks following the election were marked by rampant disinformation campaigns about alleged but unproven insecurities in the electoral process. This clearly demonstrates that there is work to be done not only to secure elections but to convince the public that elections, and election results, can be trusted. This involves making real improvements to cybersecurity and electoral processes, as well as engaging in voter education about how elections work and what safeguards exist to secure them.

For this report, we explore the challenges of maintaining security in U.S. elections and how election officials and policymakers might best address them. We examine the vulnerabilities in various components of the election infrastructure used in the biennial national elections. We analyze an array of events and situations that arose in recent elections including those in 2020, and we offer best practices for a U.S. elections cybersecurity agenda. While focused on American elections, we hope that some of the findings here can also provide guidance for other countries with different election infrastructures and needs.