Call Detail Records: “Does the NSA Know Where You Are?”

Since the Guardian reported that the NSA collects the “call detail records” (CDR) of millions of Americans, a lot of conflicting information has emerged about what exactly the NSA can scoop up under Section 215 of the PATRIOT Act. What exactly do we know about the call detail records that the NSA ordered Verizon and other carriers to hand over? Absent any information from the NSA, what can we infer based on what we know about CDRs in other contexts?

Phone companies use CDRs to bill their users. For instance, routing information on a landline call indicates when to bill a customer for using long distance services. For mobile services, companies must know how long a user was on the phone and whether the user made any ‘roaming’ network connections. To determine roaming status, companies record which cell phone towers handled the call – generally the cell phone tower closest to the caller’s physical location. With smartphones, companies collect volumes of additional Internet detail records to monitor users’ web-based services and data plan usage.

In terms of the specific call detail records requested under PATRIOT Act Section 215, the Verizon court order requires Verizon to disclose:

- comprehensive communications routing information, including but not limited to session identifying information (e.g., originating and terminating telephone number, International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI) number, International Mobile station Equipment Identity (IMEI) number, etc.);

- each call’s trunk identifier;

- each call’s telephone calling card numbers; and

- the time and duration of each call.

The Verizon order covers both landlines and cellular phone calls. In order for a cellular phone call to successfully connect from one handset to another, it goes through a complicated routing process to ensure delivery. It must make a long journey, both over the air to a cell phone tower and then through land lines, before exiting at another tower to be transmitted to the recipient’s handset. For billing purposes, the phone company must record, at a bare minimum, the point at which the call enters the cellular system, both at the beginning and end of the call. If a caller is moving between coverage areas these entry points will be different cell IDs; if a caller is stationary they’ll be the same. For certain cellular networks the trunk identifier could identify the specific tower from which a call originated, which can locate the calling phone. Ultimately, the NSA’s definitions for “comprehensive routing information” and “trunk identifier” determine the degree to which this data contributes to location tracking.

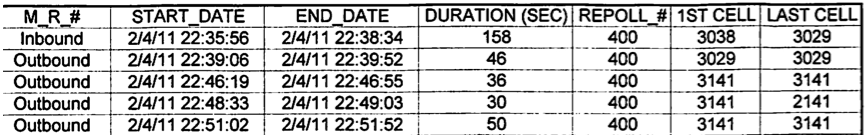

Call detail records reveal the cell towers used to route a cellular call. Prosecutors in criminal litigation use this attribute of CDRs to place a suspect at the scene of a crime. Shown below is a sample of the call detail records that Sprint handed over in response to a standard court order in U.S. v. Graham, a Maryland case in which the government sought cell site location information for a 221-day period. In the far right columns, the standard ‘first’ and ‘last’ Cell IDs are listed. Also listed is the repoll number, indicating which phone switch handled the call. Paired with a cell phone coverage map for the area – readily accessible without a warrant – the sparse, far-from-comprehensive routing information in these CDRs reveals the latitude and longitude of the cell sector each call is routed through. This certainly falls into the category of cell site tower information.

Administration officials adamantly deny that the NSA is getting phone location from this program. During the House Select Intelligence Committee briefing on June 18, Gen. Keith Alexander stated, “We don’t get any cell site or location information as to where any of these phones were located.” In response to questioning from Rep. Pompeo later in the hearing, Alexander said the NSA has no knowledge of any location information “beyond the area code” under Section 215. A week later at an American Bar Association panel, Office of the Director of National Intelligence General Counsel Robert Litt reaffirmed, “I want to make perfectly clear we do not collect cellphone location information under this program, either GPS information or cell site tower information.” Both standard CDR releases – which include Cell IDs – and the Verizon court order itself – which does not specifically exclude location from elements required in a CDR – seem to stand in contrast to all of these statements.

The Administration has secured orders that require cell phone service providers to turn over information that locates a cell phone user, and the Administration denies that it uses the program to “collect” cell site tower information. It is highly unlikely that the NSA has an agency-specific definition for call detail records under Section 215 that is more restrictive than what is typically used for collection by law enforcement with no more than a subpoena. Far more likely, and far more unsettling, is that the NSA is simply being duplicitous with the American people yet again.